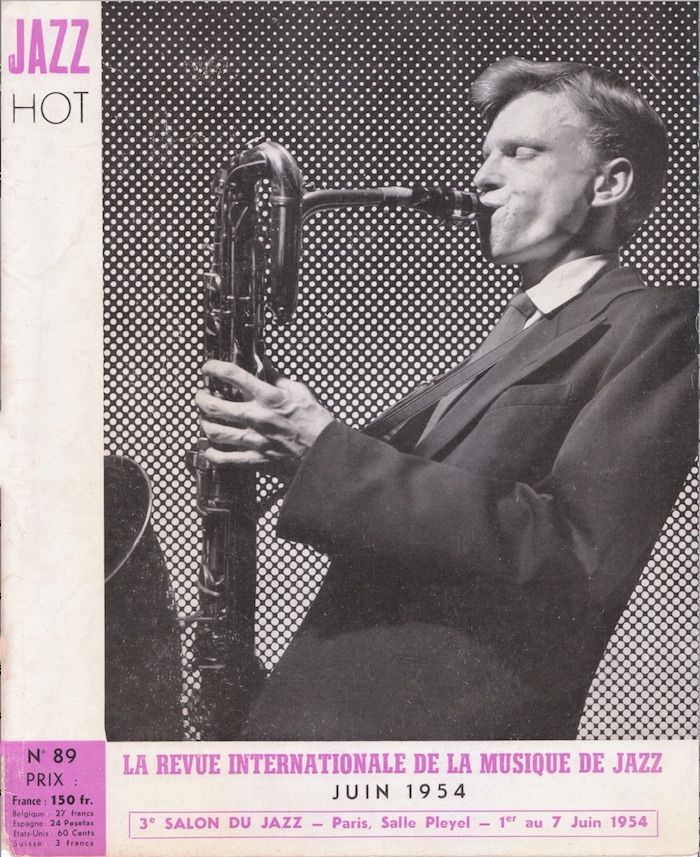

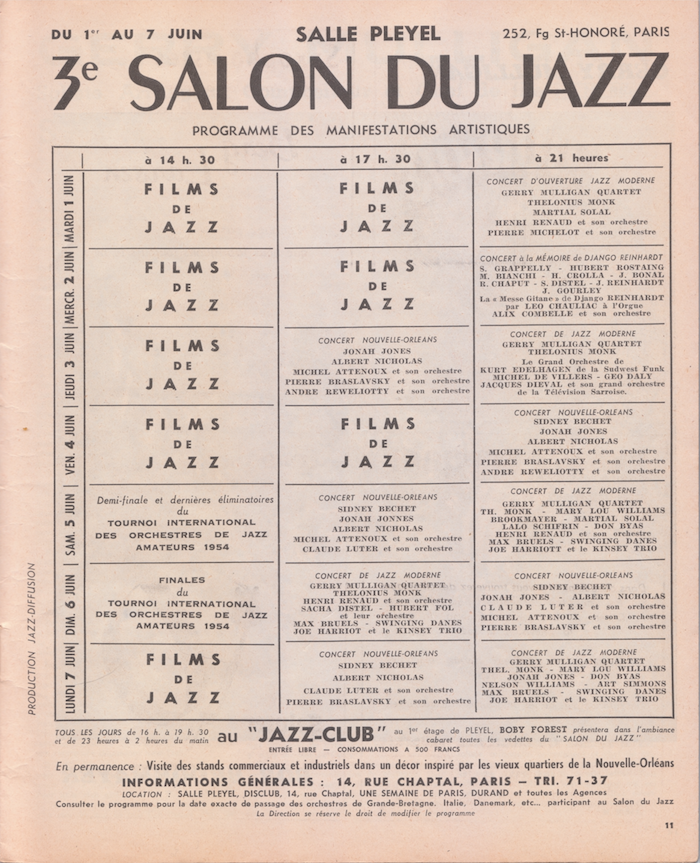

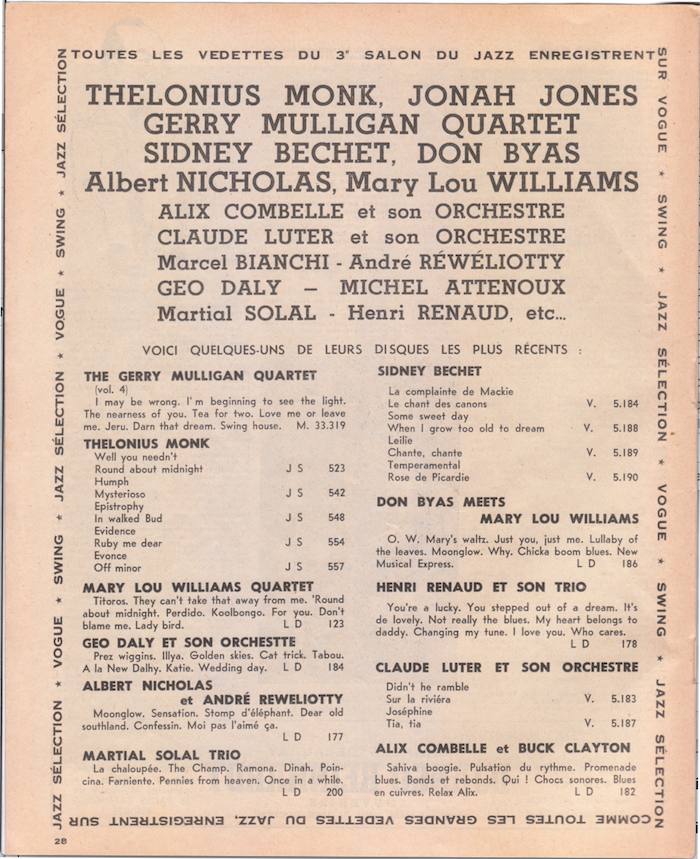

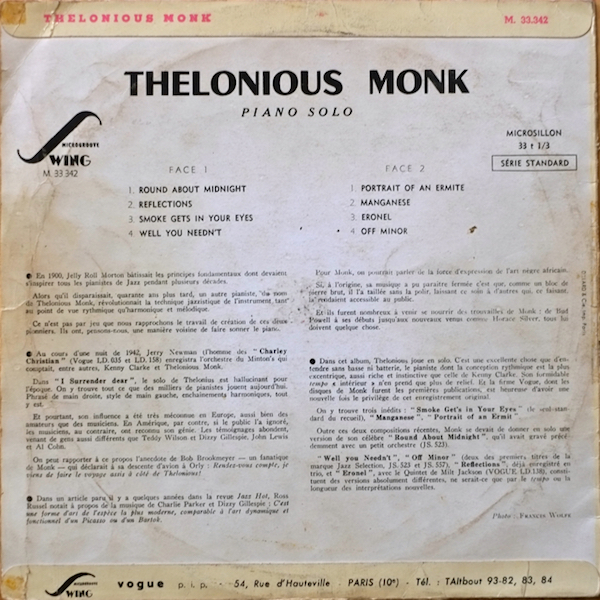

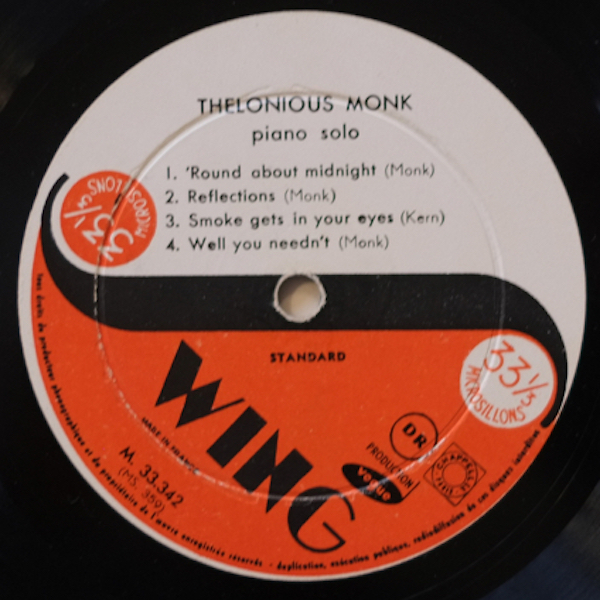

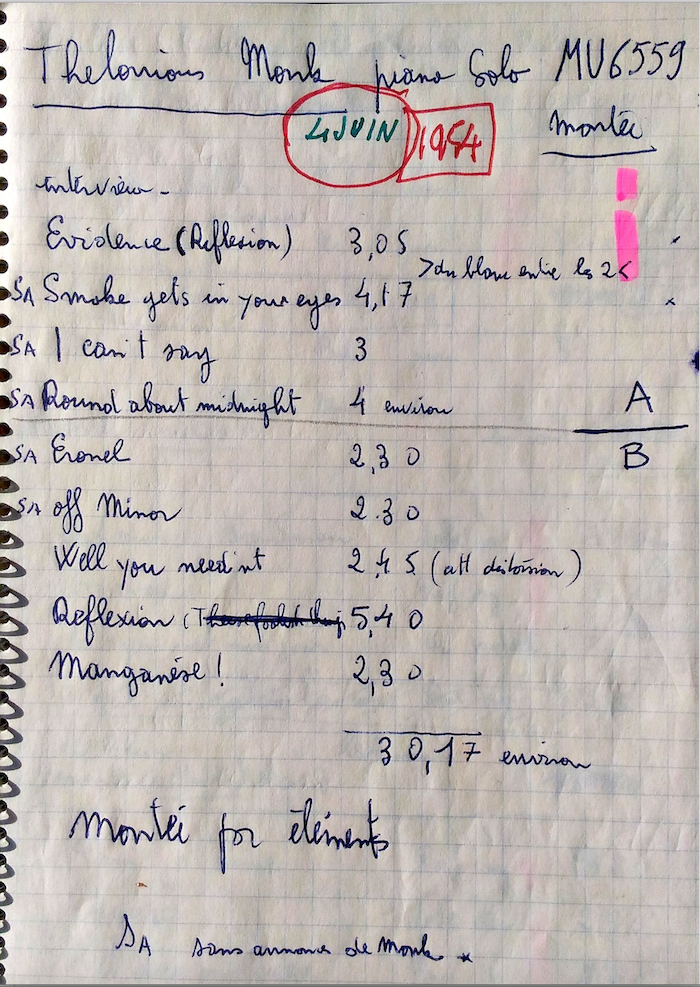

The recording of the first performance that Thelonious Monk gave in France (it was also the concert that opened the 3rd edition of France's International Jazz Salon on June 1st 1954) came to light by accident. In 2016, I had a proposal from Daniel Baumgarten, who was in charge of jazz at Sony Music (the label holding the rights to the Vogue catalogue), to reissue the solo recording Thelonious Monk, Swing M. 33.342 (Vogue), in March 2017 to coincide with Monk's centenary year. The different sequences of the recording that had appeared in discographies and reissues had always been problematic for me, as they were all different and there seemed to be no documentary evidence to back them up. I suggested that we pay a visit to our friend André Francis, who had produced the recording with Marcel Romano, as we were already working on another project with François Lê Xuân, Alain Tercinet and Fred Thomas, (cf. “Les Liaisons dangereuses 1960, musique produite par Marcel Romano" Sam Records/Saga), and

we wanted to learn more about Monk's meeting with Marcel Romano. André pulled out “his notebooks" and we had our information on the sequencing, date and place of recording (see below).

To find the original tape we sent a request to the tape library for all the tapes marked “Monk," without referring to any titles or reference numbers whatever, as is customary in such cases, and this led us to examine all the tape-boxes in the archives of Vogue (Sony Music) with "Monk" on the label. And among these was the original tape and one which turned out to be the first concert given by Monk at Salle Pleyel. When we listened to the tape we discovered that this music recorded in 1954 sounded a great deal better than reports in the French and international press and witnesses at the time would have you believe.

When I consulted the latest biography to date (Robin D.G. Kelley, “Thelonious Monk: The Life and Times of an American. Original," New York Free Press, 2009), I realized that certain accounts were largely inaccurate, particularly the factual testimony of Jean-Marie Ingrand, and so I decided to verify the information that had been published, cross-referencing articles in magazines and books that referred to Monk in France prior to 1955.

What follows below is an attempt to gather, consolidate and correct previously published information. Among other things, it (a) specifies which discs were available on the French market and those that were not; (b) demonstrates that Thelonious Monk's appearance at the Salon was not "last minute" at all, as written by Kelley, but advertised beforehand and referred to in various communiqués (along with Gerry Mulligan and Jonah Jones, Monk was one of "the three stars of this series of manifestation" (in ‘Combat,’ Monday 31 May 1954, p. 2.; “Three ‘high-profile musicians’ coming from the United States for the 3rd International Jazz Salon" with photo, Le Figaro, Tuesday 1st June 1954, p. 9; (c) shows that Jean-Marie Ingrand's memory was at times confused[•], and (d) also indicates that despite the interest shown in Monk by Charles Delaunay and Léon Cabat[•], the Vogue company wasn't that active concerning Monk, presumably due to a lack of support from the editors of Jazz-Hot.

What we did find, finally, gives credit to Ny Renaud for knowledge of the jazz scene; far from being in Henri Renaud's shadow, she played a major role in the story behind these events[•]. We would also like to say that, at this point in our research, a number of reported "facts" are still in circulation but cannot be confirmed for want of clear sources.

Daniel Richard

English translation by Martin Davies

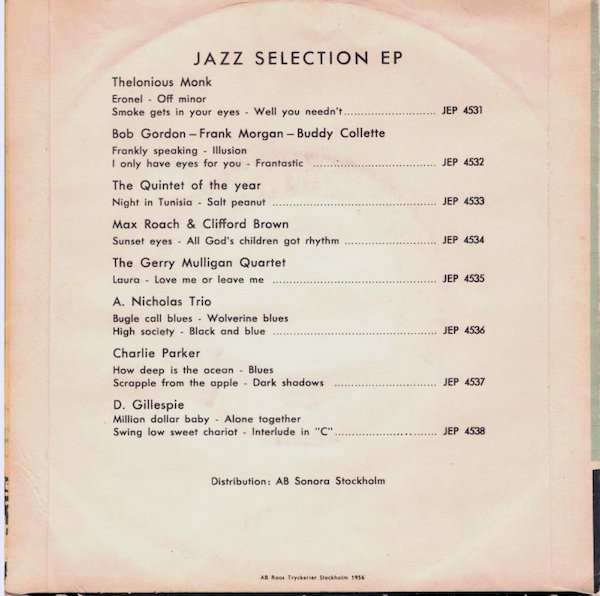

Recordings of Thelonious Monk released in France and French-speaking press appreciation before his first visit in May 1954

Reviews of Recordings As a Sideman

First reviews of Thelonious Monk’s music[•], as the accompanist of Coleman Hawkins, whose two disc were advertised in Jazz-Hot, mars 1949, p. 22 (reference “with Thelonious Monk”):

Jazz Selection, Coleman Hawkins Quartet J.S. 510 : On the Bean / Recollections.

Publié en mars 1949[•].

Voici quatre faces du quartette Hawkins, datant de 1944. En fait, ce quartette a plutôt l’allure d’un trio, car le batteur semble être absent. Du moins n’en perçoit-on pas la présence.

La première face, On the Bean, est une improvisation basée sur le célèbre thème de Whispering. Hawkins, en pleine forme, prend trois chorus pleins de verve où l’on retrouve toutes ses qualités d’invention et de punch et sa merveilleuse sonorité.

Cette face nous permet d’entendre enfin le fameux « pape du Be-Bop », Thelonious Monk, peu connu en France, mais qui jouit d’une grande réputation parmi les musiciens américains. Malgré des idées originales, sa technique limitée l’empêche de s’affirmer comme soliste. C’est plutôt un excellent accompagnateur be-bop, dont la personnalité ne semble d’ailleurs guère s’accorder avec celle de Hawkins.

Le verso, Recollections, joué sur tempo lent, nous montre cet aspect particulier de Hawkins alternant les phrases sur le temps et les phrases rapsodisantes. Le solo de ténor est d’une grande inspiration mélodique, et typique du jeu de Hawkins sur tempo lent …

Here we have four sides by the Hawkins quartet dating from 1944. This quartet sounds more like a trio in fact, as the drummer seems absent, or at least you hardly notice his presence.

The first side, On the Bean, is an improvisation based on the famous Whispering theme. Hawkins is in fine fettle, playing with verve on his three choruses where you can hear all his inventive qualities together with his punch and that wonderful sound.

Finally, this side allows you to hear the famous "Pope of Be-Bop,” Thelonious Monk; he was little-known in France but already had a great reputation among American musicians. Despite the originality of his ideas, his technical limitations prevented him from establishing himself as a soloist; he was an excellent bebop accompanist, rather, whose personality, in passing, hardly seems in tune with the character of Hawkins.

The flipside, Recollections, taken at a slow tempo, shows us this particular aspect of Hawkins' playing, where he alternates phrases on the beat with others where he rhapsodizes. The tenor solo has great melodic inspiration and is typical of the way Hawkins played a slow-tempo …

Jazz Selection, Coleman Hawkins Quartet J.S. 508 : Flyin’ Hawk / Drifting on a Reed.

Publié en mars 1949[•].

…Dans Flyin’ Hawk, sur tempo rapide, Hawkins joue avec sa flamme habituelle. Nous pouvons ici admirer son fameux vibrato haletant qui donne à son jeu une chaleur et une émotion que ne possède aucun autre ténor. On notera, dans le dernier chorus, une profonde ressemblance avec son disciple Byas.

Thelonious Monk prend ici un solo de 32 mesures fort original, que j’avoue aimer beaucoup, plus d’ailleurs pour les idées harmoniques que pour la beauté des phrases.

La quatrième face, Drifting on a Reed, sur tempo lent, se reproche beaucoup du fameux Body and Soul par la construction des phrases, mais n’atteint pas le même degré d’émotion. Hawkins y semble moins à l’aise. Il joue cependant une très belle coda.

En résumé, quatre faces fort intéressantes que doit posséder tout amateur de Hawkins.

R. A. [Robert Aubert]

« Disques », Jazz-Hot, N° 33, 15e Année (2e Série), mai 1949, p. 23.

…On Flyin’ Hawk, played at a quick tempo, Hawkins shows his usual ardour. Here we can admire his famous 'breathless' vibrato, which gives his playing the warmth and emotion that made him a unique tenor. In the final chorus you can note his profound resemblance to his disciple Byas.

Here Thelonious Monk takes a highly original 32 bar solo that I confess I like enormously, more, incidentally, for the harmonic ideas than for the beauty of his phrases.

The fourth side, Drifting on a Reed, over a slow tempo, is very close to the famous Body and Soul in the construction of his phrases, but it doesn't reach the same degree of emotion. Hawkins seems less comfortable here. He does play a very beautiful coda, however.

To summarize: four very interesting sides that every Hawkins fan should possess.

Also, in the short-lived magazine published by Eddie Barclay, Jazz News:

Jazz Selection, Coleman Hawkins Quartet J.S. 508 : Flyin’ Hawk / Drifting on a Reed.

Publié en mars 1949[•].

C’est du bon Hawkins : A) sur tempo lent, B) tempo moyen, mais le tout est, pour mon goût, en peu mou. Rares sont les occasions que l’on a d’entendre Thelonious Monk et, malgré qu’il ne semble pas être dans ses meilleurs jours, son jeu sera peut-être une révélation pour beaucoup…

This is good Hawkins: A) at a slow tempo, B) mid-tempo, but all of it lacks muscle, to my taste. The chances to hear Thelonious Monk are rare and, despite the fact he seems not to be on a great day, his playing will no doubt come as a revelation for many...

Jazz Selection, Coleman Hawkins Quartet J.S. 510 : On the Bean / Recollections.

Publié en mars 1949[•].

…Je préfère le second disque. On the Bean (Whispering) est bien enlevé. Recollections est un beau thème de W. Thomas, Hawkins y fourmille d’idées langoureuses.

Hubert Fol

« Disques », Jazz News, N° 6, juin 1949, p. 17.

...I prefer the second disc. On the Bean (Whispering) is very lively. Recollections is a beautiful tune by W. Thomas and Hawkins teems with languid ideas in this.

Georges Daniel and André Hodeir picked him for their "ABC du Jazz”:

Soliste et accompagnateur très original. L’un des précurseurs du be-bop. On the Bean avec Coleman Hawkins (Jazz Selection)

« L’ABC du Jazz : Essais d’initiation (9 et fin). Principales figures du jazz (cent noms à retenir) par Georges Daniel et André Hodeir », Jazz-Hot, N° 35, 15e Année (2e Série), juillet 1949, p. 11.

Highly original soloist and accompanist. One of the bebop's precursors. On the Bean with Coleman Hawkins (Jazz Selection).

Reviews of Recordings As a Leader

Only 5 of the first 6 Blue Note 78rpm records out of a total of 14 discs and 1 side, released in the US between January 1948 and October 1953[•], were released in France by Jazz-Disques[•]; this new company had received a license to distribute (Blue Note) as early as April 1949. The releases received a mixed reception in Jazz-Hot[•]:

Jazz Selection, Thelonious Monk Trio / Quintet J.S. 523 : Well You Needn’t / 'Round about Midnight.

Publié en avril 1949[•]

Thelonious Monk est généralement considéré comme un pianiste d’avant-garde. On l’a même surnommé « le Grand-Prêtre du be-bop ». Dans ces deux faces, il est évidemment beaucoup plus en valeur que dans les Quartette Hawkins chroniqués le mois dernier par Robert Aubert. Son jeu assez viril malgré un toucher nuancé semble axé sur une recherche perpétuelle, tant au point de vue mélodique qu’au point de vue harmonique. Style très personnel, d’un dépouillement qui rejoint celui des solos de Count Basie. L’invention est parfois déconcertante, surtout dans 'Round about; mais que de swing au verso! Dans la première face, Monk est accompagné par Gene Ramey (b) et Art Blakey (dm) d’excellente façon.

A.H. [André Hodeir]

« Disques », Jazz-Hot, N° 34, 15e Année (2e Série), juin 1949, p. 23.

Thelonious Monk is generally considered an avant-garde pianist. He was even nicknamed the "High Priest of Bebop.” On these two sides he is obviously more in favour than in the Hawkins quartet recordings reviewed last month by Robert Aubert. His rather virile playing, despite nuances in his touch, seems centred on his constant research into both melody and harmony. A very personal style, with a sobriety close to that heard in solos by Count Basie. The inventiveness is at times disconcerting, especially in 'Round about...; but what swing on the other side! On the first side Monk has excellent accompaniment from Gene Ramey (b) and Art Blakey (dm).

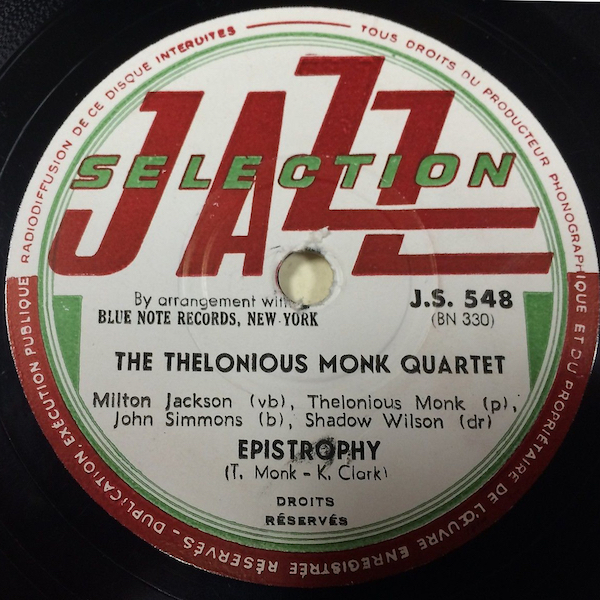

Jazz Selection, Thelonious Monk Quartet / Sextet J.S. 542 : Misterioso / Humph.

Publié en décembre 1949[•].

On ne comprend pas très bien pourquoi l’éditeur a cru devoir coupler ces quatre faces de cette façon, alors que, par la composition de l’orchestre comme par le style même de la musique, Misterioso et Epistrophy sont en quelque sorte deux faces-sœurs, qu’il eût été indiqué de réunir.

On y entend un quartette composé de Milt Jackson (vib.), Th. Monk (p), John Simmons (b), et Shadow Wilson (dm). Je n’aime guère les solos de Monk : son dépouillement pourrait bien n’être que de la pauvreté, et ses accrochages ne sont pars toujours géniaux. Mais il faut convenir qu’il a su imprimer à ces deux œuvres un caractère fortement personnel et qui n’est pas sans captiver l’auditeur.

Misterioso est un blues en si bémol. On a enregistré beaucoup de blues en si bémol depuis que le jazz existe, mais celui-ci ne risque guère d’être confondu avec quelque autre. Le thème, basé sur une sorte de sixtes mélodiques ascendantes qui s’égrènent sur les accords et « passages » du blues, est des plus curieux.

A. H. [André Hodeir]

« Disques », Jazz-Hot, N° 40, 16e Année (2e Série), janvier 1950, p. 21.

We don't understand very well why these four sides have been coupled like this, since Misterioso and Epistrophy could be sister-sides, both in the group's line-up and in the style of the music, and putting them together would seem appropriate.

In these you hear a quartet made up of Milt Jackson (vib.), Th. Monk (p), John Simmons (b), and Shadow Wilson (dm). I barely like Monk's piano solos: his sobriety could well be poverty, and those abrupt collisions aren't always signs of genius. But you have to agree that he has left a strong, personal imprint on these two works, one that the listener may find captivating.

Misterioso is a blues in B flat. People have recorded many B flat blues pieces ever since jazz has existed, but there's little risk that this one might be confused with any another. The theme, based on a kind of ascending melodic sixths that are dotted over the chords and "passages" of this blues, is most unusual.

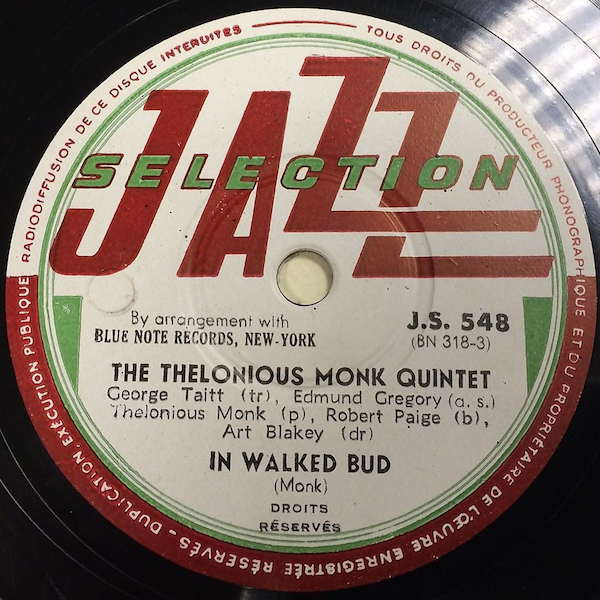

Jazz Selection, Thelonious Monk Quintet / Quartet J.S. 548 : In Walked Bud / Epistrophy.

Publié en décembre 1949[•].

On connaît déjà l’Epistrophy de Kenny Clarke. Cette version-ci est très différente, avec une introduction où le piano de Monk contrecarre par ses « trois pour deux » le rythme générale; l’impression d’ensemble est d’ailleurs un peu confuse.

Dans les deux faces, Monk vaut surtout par son jeu d’accompagnement très original et bien venu. Quant à Milt Jackson, c’est un soliste de tout premier ordre, le seul à ma connaissance qui puisse être placé sur le même plan que Lionel Hampton.

Ces deux faces seront, à ce point de vue, une révélation pour bien des amateurs français. Quant à la section rythmique, elle s’acquitte bien des tâches que Monk lui assigne.

Humph est exécuté par Idrees Sulieman (tp), Danny Quebec (as), Billy Smith (ts), Th. Monk (p), Eugene Ramey (b) et Art Blakey (dm). C’est un thème assez vulgaire, que ne rachète point une série de chorus sans grand relief. Le meilleur est le jeu de la section rythmique.

In Walked Bud joué par George Taitt (tp), Ed Gregory (as), Monk, Robert Paige (b) et Art Blakey est un disque qui « chauffe ». Les solistes ne sont pas très remarquables et il y a même quelque trivialité dans le jeu de G. Taitt. La sonorité dure de Monk y est plus en évidence que dans les autres faces : et, comme dans Humph et Epistrophy, il y abuse de la gamme par tons.

A. H. [André Hodeir]

« Disques », Jazz-Hot, N° 40, 16e Année (2e Série), janvier 1950, p. 21.

We already know the Epistrophy (version) by Kenny Clarke. This one is very different, with an introduction where Monk's piano and its "three for two" counteracts the general rhythm, which incidentally gives an overall impression of confusion.

On both sides, Monk is interesting above all for his highly original accompaniment, which is very welcome. As for Milt Jackson, he is a first-rate soloist, the only one to my knowledge on the same scale as Lionel Hampton.

From that point of view, these two sides will come as a revelation to French jazzfans. As for the rhythm section, the tasks that Monk allots to them are carried out well. Humph is executed by Idrees Sulieman (tp), Danny Quebec (as), Billy Smith (ts), Th. Monk (p), Eugene Ramey (b) and Art Blakey (dm). The tune is rather common, and a series of choruses without much relief do nothing to redeem it. The best comes from the rhythm section.

In Walked Bud, played by George Taitt (tp), Ed Gregory (as), Monk, Robert Paige (b) and Art Blakey is a recording that "cooks." The soloists are not that remarkable and there's even some triviality in the playing of G. Taitt. The hard sound of Monk is more in evidence in this title than on the other sides and, as in Humph and Epistrophy, here he goes too far in his use of the whole tone scale.

Jazz Selection, Thelonious Monk Quartet / Trio J.S. 554 : Evidence / Ruby My Dear.

Publié en décembre 1949[•].

Le premier chorus d’Evidence est joué magistralement par Milt Jackson qui est vraisemblablement l’un des plus grands musiciens bop et, avec Hampton, le meilleur parmi les vibraphonistes. Puis Monk commence un chorus, je ne dirai pas par une de ses phrases favorites, mais par « sa » phrase favorite, étant donné qu’elle revient dans tous ces disques! Elle lui plait d’ailleurs tellement qu’il la répète tout au long de cette face. Je sais que beaucoup diront que c’est d’un dépouillement génial; j’ai bien peur quant à moi, que ce soit là une pauvreté d’inspiration. C’est en tout cas ainsi que cela s’appellerait chez un Hawkins ou un Lester Young si il leur prenait fantaisie de jouer de telle manière. Monk s’affirme en tout cas ici accompagnateur original.

Ruby My Dear est un solo de Monk que je n’arrive pas à trouver génial en dépit de mes efforts. Il s’y montre assez médiocre pianiste, instrumentalement parlant. De plus, il abuse des procédés de gammes par tons, et son inspiration me semble plutôt faible. Ses deux grandes qualités sont une personnalité incontestable et un swing certain. A mon sens, son renom en Amérique parmi les musiciens vient davantage de ses dons d’accompagnateur que de ses qualités de soliste.

R. A. [Robert Aubert]

« Disques », Jazz-Hot, N° 44, 16e Année (2e Série), mai 1950, p. 28.

Milt Jackson masterfully plays the first chorus on Evidence; in all likelihood he is one of the greatest bop musicians and, with Hampton, the best among the vibraphone players. Then Monk begins a chorus, I won't say with one of those favourite phrases, but rather "his" favourite phrase, given that it comes back again on all his records! He likes it so much in fact, that he repeats it all the way through this side. I know many will say that his sobriety here is the work of a genius, but I'm afraid that this only shows poor inspiration in my opinion. It is, in any case, what it would be called in a Hawkins or a Lester Young if it took their fancy to play this way. Here, in any case, Monk asserts himself as an original accompanist.

Ruby My Dear is a Monk solo where I see no evidence of genius despite my efforts. He shows himself a rather mediocre pianist here, instrumentally speaking. Plus, his manner of playing whole tone scales is overdone, and I find his inspiration rather weak here. His two great qualities are his unquestionable personality and a definite swing. To my mind, his renown in America, in musicians' circles, stems more from his gifts as an accompanist rather than from his qualities as a soloist.

In his (critical) essay “Puissances du Jazz" ("Powers of Jazz"), a book, the Surrealist poet Gérard Legrand unreservedly provides a beautiful evocation of the music of Monk:

« Chapitre VII - Jazz et Surréalisme »

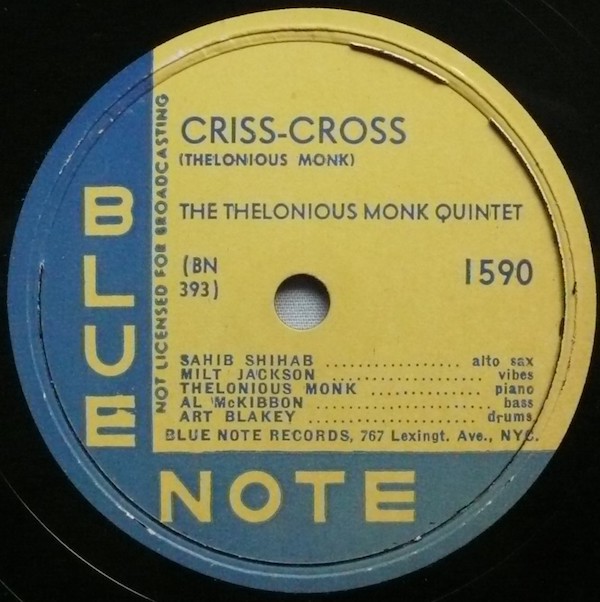

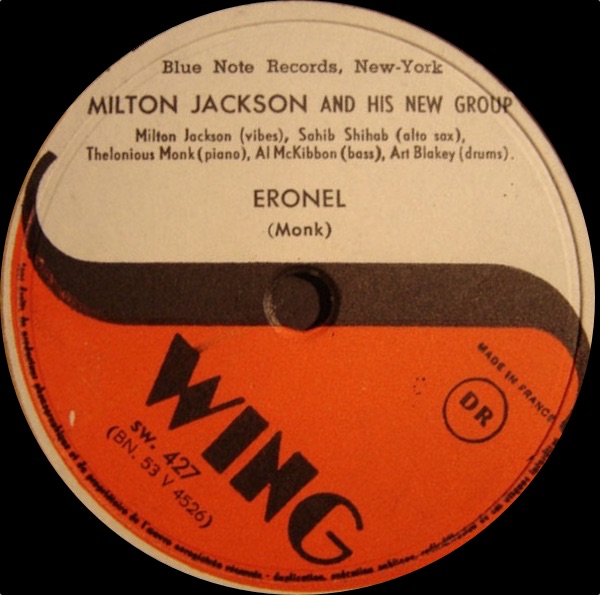

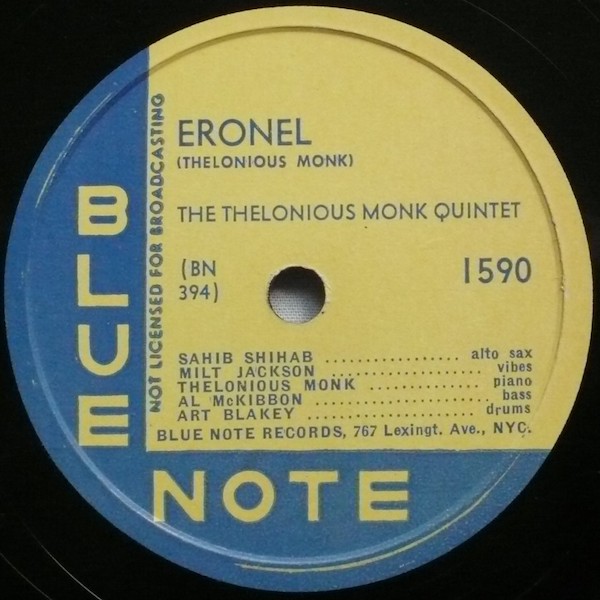

« Je terminerai ces quelques pages, dont l’allure de palmarès me gêne tout le premier, en évoquant le plus méconnu et l’un des plus originaux créateurs du jazz contemporain, c’est-à-dire Thelonious Monk. On l’entend rarement, quoiqu’il ait assez souvent accompagné de petites formations centrées sur Hawkins ou Gillespie. Mais, à Paris du moins, les disquaires sont unanimes à déclarer que la mévente a frappé ses premiers disques, et c’est certainement un des noms les moins connus du public même « averti » ou se croyant tel. En 1948, Robert Goffin, retour d’Amérique, n’en parlait que comme d’un personnage mystérieux, dont tout le monde néanmoins reconnaissait la décisive influence sur le « new sound ». Son originalité est extrême. Il impose à tous les thèmes une volonté de rigueur particulière, qui ne se situe exactement ni dans le domaine passionnel (aucune effusion, pas la moindre trace de forcing) ni dans le domaine intellectuel : c’est tout l’opposé d’un Lennie Tristano, chez qui l’attaque disparaît au profit d’un lissé continu de l’harmonie. Sa lucidité ne conclut pas à la froideur, mais à une sorte de perfection à rebrousse-poil, exaspérante, qui n’a même pas l’excuse d’être lyrique ou mécanique, et qui me permet, risquant le délire d’interprétation, de situer—seul sans doute des grands musiciens de jazz que j’aime—Thelonious Monk sur un plan éthique (« par-delà le bien et le mal » évidement). Je veux dire qu’avec Thelonious Monk, la valeur esthétique des éléments constitutifs du piano-jazz est immédiatement érigée en valeur autonome et participe de cette catégorie unique de la relation universelle où la dialectique nous contraint de situer l’Absolu. Cette perfection, sensible dans les enregistrements « anciens » de Thelonious Monk, tel Ruby My Dear et Evidence (avec Milt Jackson, John Simmons à la basse et Shadow Wilson aux drums) se pare tour à tour, dans les faces toutes récentes (début 1952) que sont Criss Cross, Eronel, avec son prologue ironique, Four in One, Straight No Chaser, d’une cruauté brillante et d’une fraîcheur d’aurore. Thelonious Monk, outre Milt Jackson en qui s’affirme le meilleur des jeunes vibraphonistes, y est entouré d’Al McKibbon (b), d’Art Blakey (dms) et de Sahib Shihab (ce doit être un pseudonyme) alto-sax dont les chorus sont faibles, mais dont les unissons avec Milt Jackson sont une révélation. On peut encore attendre beaucoup de Thelonious Monk. Dans cette musique transparaît la provocante sécheresse du sourire de la Sphinx, tandis que les éclats de bois et d’acier qui l’environnent ont la détente des serpents et ses harmonies l’acidité tonique de l’éclair. Le caractère occulte de la grande création musicale, grâce à Thelonious Monk, trouve sa revanche à l’intérieur même de ces airs de fête qui sont le jazz[•]. »

« Appendice »

« Depuis que les pages précédentes ont été écrites, j’ai pu entendre quelques faces de Thelonious Monk sur « Blue Note » américain, antérieures à la série de 1952. Dans Thelonious et Suburban Eyes, titre bizarre d’un thème d’Ike Quebec, Thelonious est entouré comme naguère dans Humph et Evonce (Jazz-Selection) par Idrees Sulieman (tp), Danny Quebec West (as), Billy Smith (ts), Eugene Ramey et Art Blakey. Dans Monk’s Mood et Who Knows, la formation comprend George Taitt (tp), Edmund Gregory (as), Robert Paige (b), et Art Blakey. Le soutien de ce dernier est partout d’une précision remarquable. La première des quatre faces est d’un humour typique : Thelonious joue environ un quart de disque avec un décalage de temps voulu, terriblement insistant, puis se retrouve sur ses pieds comme un chat-tigre jeté en l’air. Dans Monk’s Mood, il parodie Fats Waller. Les « mélodistes » d’une grande jeunesse jouent avec flamme mais oscillant entre des influences diverses. Les arrangements ne sont pas aussi nets que dans la série avec Milton Jackson, mais je tenais à signaler ces disques aux amateurs du plus « secret » des pianistes modernes. Enfin, Ask Me Now est un solo triomphal de Monk, comme Willow Weep for Me, la démonstration la plus complète peut-être de Milt Jackson. »

Gérard Legrand. Puissances du jazz. Paris: Arcanes, 1953, pp. 182-184, 216, 217.

“Chapter VII - Jazz and Surrealism"

“I will close these few pages—and I’m one of the first to be embarrassed by its 'list of achievements' appearance—in evoking the least well known and one of the most original creators in contemporary jazz, and that is Thelonious Monk. You rarely hear him even though he has rather often accompanied small groups centred around Hawkins or Gillespie. But in Paris, at least, record-shops are unanimous in declaring that his first records were hit by poor sales, and his name is certainly one of those least known to the public, even thosewho are "well-informed" or believe themselves to be so. In 1948, on his return from America, Robert Goffin spoke of him only as a mysterious character, albeit one whose influence over the 'new sound' everybody recognized as decisive. His originality is extreme. He imposes a particular demand for rigour on every tune; this is not exactly a question of passion (no effusions, not the slightest trace of forcing his hand), nor is it an intellectual matter: this is quite the opposite of a Lennie Tristano, where the attack is eclipsed by a continuous lissé or 'smoothing-out' of the harmony. His lucidity doesn't imply coldness; rather a sort of perfection that goes against the grain, exasperating, with not even the excuse of being lyrical or mechanical. It allows me, at the risk of interpreting this deliriously, to situate Thelonious Monk—no doubt he's alone among the great jazz musicians I love—on an ethical plane ("over and above good and evil", obviously). I mean that with Thelonious Monk, the aesthetic value of the elements constituting jazz piano is immediately established as an autonomous value, having something of the nature of that unique category of universal relationships where dialectics oblige us to situate the Absolute. This perfection, which can be sensed in the "old" arrangements of Thelonious Monk, like Ruby My Dear and Evidence (with Milt Jackson, John Simmons on bass and Shadow Wilson on drums) is by turns adorned, in all the most recent sides (early 1952) like Criss Cross and Eronel, with its ironic prologue, Four in One, Straight No Chaser, by a brilliant cruelty and a dawn-like freshness. Thelonious Monk, as well as Milt Jackson, becoming more assertive as the best of the young vibraphone players, is here in the company of Al McKibbon (b), Art Blakey (dms) and Sahib Shihab (it must be a pseudonym) on alto sax, whose choruses are weak, but whose unison playing with Milt Jackson is a revelation. We can still expect a lot more from Thelonious Monk. The provocative dryness of the Sphinx's smile transpires in this music, whilst the slivers of wood and steel in its environment have the thrust of serpents, and its harmonies the tonic acidity of lightning. The occult character of great musical creation, thanks to Thelonious Monk, takes its revenge in the very inside of those festive airs that are jazz[•]."

"Appendix"

"Since the preceding pages were written I've been able to listen to a few of Thelonious Monk's sides on American Blue Note which date from before the 1952 series. In Thelonious and Suburban Eyes, the bizarre title of an Ike Quebec tune, Thelonious is surrounded, as lately on Humph and Evonce (Jazz-Selection), by Idrees Sulieman (tp), Danny Quebec West (as), Billy Smith (ts), Eugene Ramey and Art Blakey. On Monk’s Mood and Who Knows, the group is made up of George Taitt (tp), Edmund Gregory (as), Robert Paige (b) and Art Blakey. The support of the latter shows remarkable precision throughout. The first of the four sides is typically humorous: for around a quarter of the recording,Thelonious plays with a deliberate, extremely insistent retard in the tempo, and then he lands on his feet like some tiger-cat thrown up in the air. In Monk’s Mood he parodies Fats Waller. "Melodists," in their extreme youth, will play with flaming passion but oscillate between varying influences. The arrangements are not as clean as in the series with Milton Jackson, but I wanted to draw these discs to the attention of fans of this most "secret" of modern pianists. Ask Me Now, finally, is a triumphant solo from Monk and, like Willow Weep for Me, perhaps the most complete demonstration to come from Milt Jackson."

News

Whereas some critics had mixed feelings, Jazz-Hot columnists Léon Kaba (Cabat, Jazz-Disques CIO) and Léo Vidalie (Léon Vidalie, Jazz-Disques Production Manager[•]) in their “Nous avons reçu de New York” articles ["We received from NY" column], and US correspondent Ralph Hofmann, were by contrast enthusiastic:

« Thelonious Monk Sextet : 'Round about Midnight / Well You Needn’t (Blue Note 543) Thelonious / Suburban Eyes (B.N. 542). Il joue rudement bien, le grand prêtre Monk : rien que pour lui, il faut avoir ces disques (et aussi pour Art Blakey aux drums). »

« Nous avons reçu de New York, par Léon Kaba et Léo Vidalie », Jazz-Hot, N° 26, 14e Année (2e Série), octobre 1948, p. 24.

"Thelonious Monk Sextet: 'Round about Midnight / Well You Needn’t (Blue Note 543) Thelonious / Suburban Eyes (B.N. 542). He plays terribly well, this high priest Monk: you must have these records just for him (and for Art Blakey on drums, too).”

"« …Thelonious Monk dont nous vous signalons le dernier disque : Misterioso / Humph, B.N. 560, disque non seulement débordant de swing, mais en plus plein d’idées amusantes. Quand le grand Monk sera-t-il vraiment apprécié? »

« Nous avons reçu de New York, par Léon Kaba et Léo Vidalie », Jazz-Hot, N° 36, 15e Année (2e Série), septembre 1949, p. 30."

"...Thelonious Monk, whose last record we drew your attention to: Misterioso / Humph, B.N. 560, a disc not only brimming ver with swing, but full of amusing ideas as well. When will the great Monk be really appreciated?"

« Blue note vient de sortir deux nouveaux 78 tours avec Kenny Dorham (tp), Lou Donaldson (as), Lucky Thompson (ts), T. Monk (p), Nelson Boyd (b), et Max Roach (dm) : « Let’s Cool One/Skippy » (1602) et « Hornin’ in/Carolina Moon » (1603). Excellents disques : entre autres, « Skippy » comprend un excellent solo de Monk. Dans « Let’s Cool » on peut entendre quelques beaux ensembles de Dorham, Donaldson, Thompson, Boyd. »

R. H. (Ralph Hofmann)

« Jazz-Hot Magazine : Le Disques aux U.S.A. », Jazz-Hot, N° 81, 19e Année (2e Série), octobre 1953, p. 20.

"Blue Note has just released two new 78s with Kenny Dorham (tp), Lou Donaldson (as), Lucky Thompson (ts), T. Monk (p), Nelson Boyd (b), and Max Roach (dm): "Let’s Cool One/Skippy” (1602) and "Hornin’ in/Carolina Moon" (1603). Excellent records: among other things, "Skippy" includes an excellent solo from Monk. In "Let’s Cool" you can hear some beautiful ensembles with Dorham, Donaldson, Thompson, Boyd."

Mentions

Before the expected article devoted to Monk alone there were these measured comments from Lucien Malson & Jacques Hess in Jazz-Hot which were general comments containing references to Monk:

« Diversité de l’école Bop »

« La première de nos remarques sera pour Thelonious Monk qui occupe une place à part. C’est en effet un « cas ». Car malgré sa très grande originalité : dans les thèmes (Humph, Evidence) et notamment dans le traitement du blues (Misterioso, avec ses montées en sixtes), dans la phrasé, si abrupt, dans l’harmonie, l’arrangement et l’atmosphère générale, il est remarquable qu’il n’a aucune influence direct appréciable par nous. Il n’est pas possible de parler d’une « école Monk ».

Il semble bien qu’il existe ensuite et à l’écart de Monk, ce qu’on peut appeler désormais un classicisme bop, directement issu de Parker-Gillespie et que nous illustrons ici par les groupements de Bud Powell et Tadd Dameron qui présentent des point communs… »

« Regards sur le jazz actuel par Lucien Malson et Jacques Hess », Jazz-Hot, N° 51, 17e Année (2e Série), janvier 1951, pp. 8, 9.

"Bop School Diversity"

"The first of our remarks is for Thelonious Monk, who stands apart. Indeed, his is a particular “case.” For despite his very great originality—in the tunes (Humph, Evidence) and notably in the treatment of the blues (Misterioso, with its ascending intervals in sixths), in the phrasing, in harmony, arrangement and general atmosphere—it’s remarkable that he has no direct influence that we can appreciate. It's not possible to speak of a "Monk school.”

It does seem that there exists (after Monk and in the background) what one can from now on call a bop classicism, in a direct line down from Parker-Gillespie, and one that we can illustrate here via the groups of Bud Powell and Tadd Dameron which present common aspects…."

« On ne peut, à la fois, aimer le jazz et, sans amertume, dénoncer la crise qu’il subit… Parallèlement à cette chute au moins apparente des grandeurs, l’affermissement de talents plus modestes ne paraît pas niable. De très bons musiciens, nous n’en avons jamais autant connus. Sans revenir sur l’éclosion de personnalités telles que celles Getz, Cohn, Sims, Eager, Stewart, Moore, qui sont tous des petits enfants de Lester, il faut prendre pour exemple la maîtrise accrue d’un pianiste comme Monk. Monk n’a cessé, entre vingt autres artistes, d’améliorer se technique et en même temps de parfaire son langage. Ses gravures de 1951 : Ask Me Now, Criss Cross, Eronel, Four in One, Straight no Chaser dépassent toutes celles que nous connaissions de lui. Ce sont des œuvres délicates, d’une extrême fraîcheur mélodique, d’un bop assagi. Mais ce dernier mot nous replace au cœur de la crise. Puisqu’on ne peut signaler que des secteurs calmes, c’est que la création n’est plus qu’une transformation. Le drame, c’est l'absence de toute émergence… »

« Chronique de Lucien Malson : Situation du jazz », Jazz-Hot, N° 69, 18e Année (2e Série), septembre 1952, p. 9.

"You can't love jazz and, at the same time, denounce the crisis it is undergoing without some bitterness…. In parallel with the fall, at least in appearance, of its glories, the consolidation of more modest talents can't be denied. We have never known so many musicians who are very good. Without going back on the hatching of personalities like Getz, Cohn, Sims, Eager, Stewart and Moore, all of them Lester's grandchildren, you have to consider for example the increased mastery of a pianist like Monk. Monk, of around twenty other artists, has bettered his technique constantly, and perfected his language at the same time. His 1951 recordings—Ask Me Now, Criss Cross, Eronel, Four in One, Straight No Chaser—all go further than any of those we knew. They are delicate works, pieces with an extreme melodic freshness, bop that has become subdued. But that last word brings us back to the heart of the crisis. Since we only have sectors of calm to indicate, it's because creation is now no more than transformation. The drama in this is the absence of all emergence….”

First Feature Article

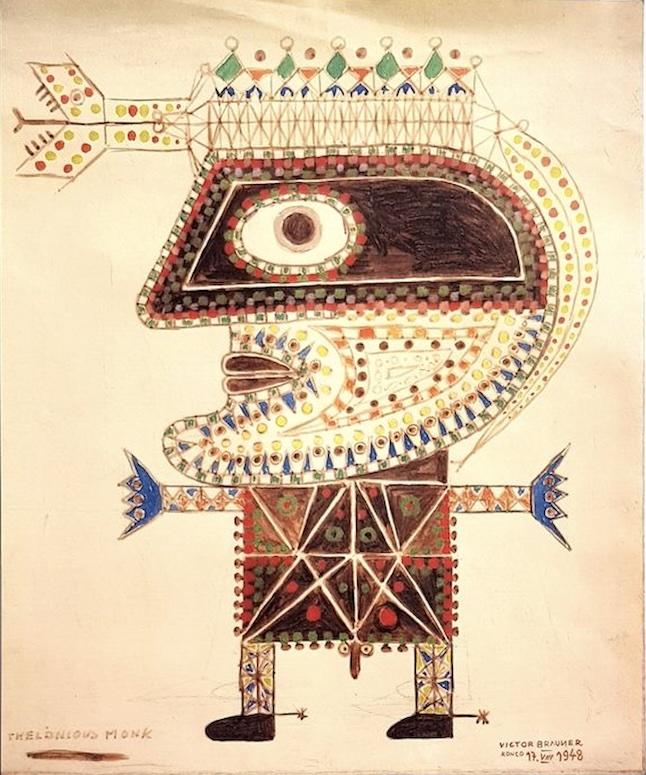

But then, instigated by Alfred Lion, came this feature written by American graphic artist Paul Bacon, a friend of Monk “It focused on Monk’s personality” said Bacon[•]. It was first published (translated into French by Boris Vian) as, “Portrait de Thelonious Monk par Paul Bacon,” in Jazz-Hot, N° 36, 15e Année (2e Série), septembre 1949, pp. 6-8. Two months later the original article appeared in The Record Changer, , Vol. 8 N° 11, November 1949:

Even the worst enemies of the man know as the “High Priest of Bebop” are forced to admit that he is, after all, a remarkable fellow. It has become fashionable to think him a greatly overrated musician, something of a charlatan, a mystic whose very mysticism is calculated to conceal a rather prosaic flaw: poor musicianship. That is utter nonsense.

There is no doubt that Monk is a man without conventional scope, without the sense of the opportune, devoid entirely of the deft imagination which Dizzy Gillespie turned into an even more valuable property than his talent, by capitalizing on the physical oddities of the bop school, with great good will and ingratiating theatrics. Lack of that perception, and élan, is serious in the music business. It leads to other lacks which, though they aren’t aesthetically noticeable, are not conducive to health and happiness: lack of things like money.

I don’t pretend to hold any brief for the things Thelonious has done to, and for, himself, nor do I intend to demonstrate that he is in reality a mild, virtuous and misunderstood man. People have knocked themselves out in his behalf, time and again, without producing any permanent good, not because of any maliciousness on Monk’s part, but because the chasm separating their senses of value from his is too great. It is better to be an amateur admirer than a promoter, in Monk’s case.

I have a choice here between writing about Monk as he is, or as he seems to be, and is generally thought to be. There isn’t any great difficulty about it, because both sides are fertile ground; the stories merely differ in plausibility. The trick to making a genuine legend out of an artist is quite simple—you need only to describe him in comparison with so-called “normal” people, if he is slightly eccentric, and, if he is not, describe his remarkable normality in comparison with the weird behavior of other artists. Thus, in Thelonious’ case, staying up for 72 hours at a stretch and then sleeping for 48 may well be considered unusual (if he did it continually, which he doesn’t, he could rest on those laurels alone), like many other things he does, unless you remember that he is a musician, that his personal life is that of a musician and not a bank clerk.

Nonetheless, there are aspects of Monk’s personality which no amount of logic can solve. He is undoubtedly a very selfish man (this quality, too, is not at all unique among artists), and the business of having the world revolve around him has caused him to see things in a remarkably direct fashion—very much in the manner of a child. The process of becoming mature requires a hell of a lot of concessions, usually called “adjustments,” and he has never made many. In this way, the formality of wearing clothes is inexplicable to a child, just as the formality of musical structure is inexplicable to Monk. I think that some subtle facet of his mind realizes that he has this quality, and that he cherishes it.

A self-absorption as profound as Thelonious’ produces some wonderful anecdotes, many of which have been printed over and over; my favorite is an incident I was spectator to, and which has never been recounted, as far as I know.

There is, in Harlem, a monstrous barn of a dance-hall called the “Golden Gate”; quite a number of affairs are produced there every year, and the usual system is to have two alternating bands working—in the last few years the two bands have been one bop group and one Calypso band. (There are a couple of remarkable Calypso bands in New York, playing a real powerhouse music which is closer to Harlem in 1928 than Trinidad in any year.) The occasion I’m thinking of took place there in 1947, almost exactly two years ago. Macbeth’s calypso contingent shared the stand with a bop sextet fronted by Monk; the boppers were second in line, so, after a long set by Macbeth, Monk’s band wandered desultorily to the stand.

Monk fussed with the piano, discovering that it was a pretty venerable instrument (when he sits at a piano there is a dead key on it—no matter how recently the thing was in perfect condition. He accepts this as one of the penalties of genius) and making faces at it as he sounded notes at the other musicians’ request. Close examination showed him that the pedal post was shakily attached; he jiggled the whole piano apprehensively, then shrugged his shoulders and concentrated on some music left behind by Macbeth’s pianist.

A little later, I became aware that Thelonious was doing something extraordinary—tying his shoe or waving to somebody under the piano; as I watched, mesmerized, I saw that he was yanking at the pedal post with all his might (first he kept up with the band by reaching up with his right hand to strike an occasional chord, but he had to apply himself to the attack on the post with both hands, and get his back into it, too). There was a slight crack, a ripping sound, and off came the whole works, to be flung aside as Monk calmly resumed playing. He never looked at it again, but when Macbeth’s man came back on the stand he stopped short, stunned. It was obvious that here was a new experience, something outside the ken of a rational man; for the rest of the evening he looked upon Thelonious with a new respect.

It is generally something much like the above bit of business which cause to look on Monk with a new respect; nothing is quite so arresting as a man who actually doesn’t give a damn, even if you think he is acting, and how do you prove that?

Take off Thelonious’ famous glasses and you will look hard to find your eccentric High Priest of Bebop; they are his armor and his shield. Most people are shocked to discover that he does, after all, have eyes like their own—it’s so easy to think of him as a man with a gold-plated brow and two-inch black discs for eyes. There isn’t anything fragile about him, mentally or physically, as his reputation for being able to take care of himself will attest. A necessarily iron constitution is supported by a six-foot, 175-pound frame, which he drapes in double-breasted suits exclusively, most of the time with the coat unbuttoned. He moves slowly, very slowly, under any conditions; at his initial concert, in New York’s Town Hall, he had to walk approximately fifty feet to the piano, after being announced; he emerged from the wings with a deliberate, measured step, taking an age to reach the Steinway. Before he had completed the necessary ceremony of bench-adjusting, pedal-testing, and coattail-draping, the audience was in a state of prostration. This was not a matter of stage presence, or lack of it; only a perfect sample of the deportment of Thelonious Monk. As he puts it, “you have to be yourself—if you try to be different, you might miss your cues.”

At any rate, this man, unmalleable, exasperating, sometimes perverse to the point of justifiable homicide, is the man who casually formed the nucleus of the group which surprised itself by changing, at least temporarily, the direction of jazz. That was ten years ago.

Minton’s Playhouse, on Harlem’s 118th Street, is like many another birthplace of famous people and events—it doesn’t look like much. Inside, though, there is an atmosphere hard to find anyplace else in New York; an ease, a lack of the professional gimlet-eyes nightclub bandits, whose only salable commodity is an obsequiousness available to one and all, for a small consideration. There have also been, at various times, a dapper waiter named Romeo, who was as likely to dance for the customers as bring them drinks, and many young musicians working for a living; in 1939 they include Kenny Clarke and Thelonious Monk.

I might add here that Monk’s part in the whole history of bebop began long before 1939. In fact, as he tells it, he was playing essentially the same way he does now in 1932, when he was fifteen years old. His conception is not something that grew out of what he felt was a need for something new in music—he just played that way. His ear was hearing between the lines of its own accord, and that nonconformist ago told him that what he heard was perfectly valid. Time seems to have borne him out.

Too many stories have written about the genesis of bop at Minton’s; the footprints are all obscured, and I say why not? All the recounting of who played what for whom, and who picked it up, and who sat in and said “Man, this is it!” is producing some of the asinine squabbles which are the curse of traditional jazz. It seems definite that Monk and Clarke are chiefly responsible, and Monk has the advantage, historically, because he’s a pianist and Clarke is a drummer. I doubt that either of them, or anyone else, knew what they were doing, saw anything momentous on the horizon, or even cared particularly.

Monk is fundamentally a catalyst, a well-spring; he is consistently interesting whether he’s playing or not. The complex personality which makes his behavior unpredictable has made his music stimulating to gifted and receptive men like Parker and Gillespie; that personality is unchangeable, the stimulus is unfading. He’ll have both when he’s ninety years old.

Those are the attributes he had at Minton’s, and they made him a source, something fundamental, therefore priceless. Any new enterprise requires a certain personnel to be vital: several people who grasp because their sophistication tells them that here is a direction their machinery is admirably suited to travel in, and at least one who is here because he is unable to do anything else, the man with an honest germ of an idea. Monk fits neatly into the latter category; not a virtuoso, but a creator. He can’t sell his product, but there are salesmen who can, and do, even, though some may not believe in it simplicity.

Well, what is his product? It is something quite fragile and intangible, like the quality in the stories of Virginia Woolf and Gertrude Stein. In fact, there have been many times when Monk has offended delicate ears with his pianistic assertion that a theme is a theme. He is perfectly aware that he has nothing new to say, no revelations to make to anyone; it is the simplest thing in the world to say “all he’s done there is to play a G7th instead of, etc…” which is like saying that all Cézanne did is to translate nature into cones, cubes and spheres, and what’s so remarkable about that?

Listen to Thelonious and you hear a man listening to himself, playing variation on what he hears, so that you never really are in contact with his immediate impressions; it’s a little like watching an essentially right-handed but ambidextrous man draw with both hands at once—the right hand’s effort is calculated and familiar, but the left hand’s, though it almost follows suit, has a weird distortion; it’s the same thing, but different, and it is likely to be more interesting.

The identity of a tune is like the identity of a word—it remains itself only as long as it is scrupulously kept in its proper place, with its proper emphasis; a great many ingredients go into recognition of either one. Everyone has had the experience of having a word suddenly become a series of foreign letters utterly unrecognizable; in Monk’s hands, a well-worn tune may dissolve into that same unreality. For instance, “Liza” is a song I’ve always known and liked, and however I heard it, it was always indisputably “Liza,” with connotations of words, situations and sensations; but I heard it for the first time when Monk played it, because he is under no such hallucinations about any melody. What I have described is not the same thing as improvising: to play exhaustive variations on “How High the Moon” is not the same as to reconstruct it entirely, any more than closing your eyes makes you see as a blind man sees.

Monk’s product is essentially simplicity. Because of it, he is a provocative musician, one with whom other musicians play well—sometimes better than they ever have. Recognizing that he had something beyond a reputation to offer, Blue Note Records, a firm of almost suicidal integrity, decided to take the plunged and make some records with him. The idea bore fruit in more ways than one, because they immediately discovered a whole uneaten side of the evil apple which is bebop—young musicians, without reputation, who were following the avant-garde Gillespie and Parker circles, and bringing with them something of their own. They discovered that Monk always knew of a guy “who could blow,” trumpet, tenor, alto—whatever was required. Alfred and Lorraine Lion and Frank Wolff were, for a time, father, brother, moral support and employment agency for Thelonious and his crew, and there were some fantastically messed-up moments for all parties during the time the records were being cut.

The titles have the same charm as the music—“‘Round about Midnight,” “In Walked Bud,” “Humph,” “Ruby, My Dear,” “Evonce,” “Well, You Needn’t,” “Suburban Eyes,” to name a few; the first one was “Thelonious,” which one reviewer described as “oddly affecting,” and that’s pretty close.

During the time that these records were made, Monk went back to work at Minton’s with a quartet which has always been one of the high spots for me in the frenetic life of bop: Edmund Gregory (Shihab, as his adopted Moslem brethren call him) on alto, Al McKibbon on bass, the amazing Art Blakey on drums, and Monk. That was a perfect unit, unlike any other, before or since; they played no tunes but their own, in no way but their own; they did more rhythmically, than any musical group I ever heard anywhere; and they kept improving until the inevitable break-up came, after too short a time. That band at Minton’s made an era of its own, much as Jimmy Noone’s did at the Apex Club.

I’ll finish by saying that in listening to Monk, the same advice applies as is given to fans of traditional jazz, on hearing bop for the first time: forget what you know, don’t compare—listen. Monk is likely to be as jarring a departure from Dizzy Gillespie as Dizzy is from Louis, and yet he may hit you right away. An open ear is a wonderful thing.

“The High Priest of Bebop: The Inimitable Mr. Monk, by Paul Bacon,” The Record Changer, Vol. 8 N° 11, November 1949, pp. 9-11, 26.

Reproduced in The Thelonious Monk Reader. Edited by Rob van der Bliek. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001, pp. 57-62.

The Last Blue Note Release

This feature article in form of a promotional article will not be enough to convince potential buyers, and at the end of the year, after a final release (of which we were not able to find a review):

Jazz Selection, The Thelonious Monk Sextet / Trio J.S. 557 : Evonce / Off Minor.

Released January 1950[•].

The next mention of Monk in a Jazz-Hot, Vogue advertisement will be in the form of a newsletter, Vogue Actualités, July-August 1952:

« Le Bop est Mort (sur un air connu) »

« C’est la raison pour laquelle Thelonious Monk vient d’enregistrer [?] une séance que les dirigeants de la firme « Blue Note » considèrent comme sensationnelle. La formation comprend Sahib Sahib [sic] (as), Milt Jackson (vib.), Al McKibbon (b), Art Blakey (dm). Aux dernières nouvelles, le « Thibétain » se portait fort bien et continuait allègrement à démolir des pianos. Vaut-il mieux jouer cool ou des blues à treize mesures? »

Ad, « Vogue Actualités : Juillet-Août 1952 », Jazz-Hot, N° 68, 18e Année (2e Série), juillet-août 1952, p. 22.

"Bop is Dead (after a familiar tune)"

"This is the reason why Thelonious Monk has just recorded [?] a session that Blue Note's management considered sensational. The group included Sahib Sahib [sic] (as), Milt Jackson (vib.), Al McKibbon (b), Art Blakey (dm). According to the latest news we have, the ‘Tibetan’ was in great shape and still bent on destroying pianos. Is it better to play cool, or 13-bar blues tunes?"

No Blue Note records would be released in France until December 1955[•]. Likewise, no Prestige record by Monk would be manufactured and distributed in France before January 1956[•].

From Switzerland and Belgium

The most glowing, enthusiastic reception given to Monk's music appeared in the two modest French-language inserts (one or two pages) in Jazz-Hot, the magazine of Belgium's Hot Club, after November 1948[•] (Editor-in-chief, Carlos de Radzitzky), and in the Swiss Jazz-Revue after February 1949[•]. Both, apart from specific local content, had news and reviews of records imported from the USA:

Jazz-Revue in Jazz-Hot by Jean-Jacques Finsterwald general representative in Switzerland of Jazz-Records[•], and composer and pianist Julien-François Zbinden:

On associe volontiers le nom de Thelonious Monk aux fameuses séances du « Minton Playhouse » (208 West 118th Street, N.Y.) où furent élaborées les bases d’un nouveau style appelé communément Be Bop; on dit même que son influence fut prépondérante et qu’il contribua, pour la plus grande part, à l’élaboration des bases sur lesquelles reposent les tendance du « New Sound ». Quoi qu’il en soit, les rares disques gravés par Monk nous révèlent un des pianistes les plus originaux et les plus imaginatifs qu’il nous ait été donné d’entendre.

Thelonious Sphere Monk est né en 1918 à New York [sic], d’une famille qui ne compte pas d’autre musicien. Il commença ses expériences harmoniques et rythmiques dans un quartet où nous trouvons Keg Purnell à la batterie; c’était en 1939. Puis il devint le pianiste régulier du Minton’s à Harlem, une boîte que dirigeait le chef d’orchestre Teddy Hill.

En dépit de l’importance que lui accorde la Nouvelle École du Jazz (les musiciens en particulier), Monk ne connaît pas la célébrité d’un Parker ou d’un Gillespie. C’est probablement parce que ses qualités d’exécutant ne sont pas à la mesure de sa débordante imagination. On nous dépeint, d’autre part, sa proverbiale modestie et son mode de vie incompatible avec les exigences auxquelles est soumise une vedette; on raconte qu’il peut se passer de sommeil pendant une semaine, quitte à dormir trois jours et trois nuits quand il a réussi a s’arracher du clavier.

Monk fut enregistré pour la première fois en compagnie de Charlie Christian, Joe Guy, Nick Fenton, Kenny Clarke, à la fin de 1940. Il s’agit de six faces publiées en France par Polydor et intitulées « Charly’s Choice » et « Stompin’ at the Savoy ». La prise du son est défectueuse (l’enregistrement a été effectué au Minton’s par un amateur) et l’on devine plutôt qu’on y entend la partie de piano.

Le 19 octobre 1944, Monk accompagne Coleman Hawkins, avec Edward Robinson (b) et Denzil Best, dans « Drifting on a Reed », « Recollections », « On the Bean » et « Flying Hawk » enregistré par Joe Davis et que Jazz Selection vient de publier en France. Les solos de piano sont bien rares et vous trouverez la critique de ces disques dans la partie française de ce numéro.

Je passe donc à la série d’enregistrements que Blue Note a édités sous le nom de Thelonious Monk, enregistrements qui nous permettent enfin de l’entendre dans de bonnes conditions. Il s’agit de « Thelonious », « Suburban Eyes », « Evonce », « Off Minor », « ‘Round about Midnight », « Well You Needn’t », « Epistrophy », « In Walked Bud », « Ruby, My Dear », « Evidence », enregistrés avec des musiciens divers parmi lesquels relevons les noms de George Taitt (tp), Edmund Gregory (alto), Danny Quebec West (as), Milton Jackson (vib), John Simmons (b), Shadow Wilson (d) et d’Art Blakey (d), son drummer préféré.

Ces disques nous révèlent un musicien original à l’extrême, d’abord par son arythmie plus marquée que chez n’importe quel autre pianiste, puis par le souci constant qu’il semble éprouver d’étonner l’auditeur; cette recherche de l’inattendu chère au style Be Bop est poussée chez lui à l’extrême. Monk paraît éprouver un plaisir raffiné a hésiter tant sur le rythme que sur l’harmonie, il se dégage de ses solos une impression maladive.

L’utilisation systématique des harmoniques éloignées de la fondamentale amène des trouvailles heureuses, souvent géniales, mais l’entraîne parfois dans des impasses mélodiques. Grâce à ses variations rythmiques, il réussit à s’y maintenir, en attendant de trouver une porte de sortie qui n’est souvent qu’un retour opportun à un style de piano plus traditionnel comme c’est le cas dans « Thelonious ». Ce disque est d’ailleurs un exemple typique de son style : il s’obstine sur une note qu’il répète en variant les accents rythmiques jusqu’à l'épuisement de ses ressources. Au lieu d’une note, il lui arrive de choisir de petits motifs qu’il répète dans divers degrés (In Walked Bud).

Son jeu est simple, son style sobre et dépouillé; il utilise très peu les accords et concentre toute son attention sur une main droite à style monodique. En dépit de sa hardiesse, Monk utilise des structures harmoniques absolument logiques, des thèses relativement simples et le système par tons entiers, cher à Debussy qu’il applique avec à-propos.

La plupart de ces thèmes sont des compositions de Monk (bien que l’étiquette lui attribue la paternité de « In Walked Bud », on reconnaît facilement « Blue Skies »). Il est l’auteur [sic] de plusieurs morceaux bien connus, nous voulons parler d’ « Emanon » (anagramme de No Name), de « 52nd Street Theme » (un autre enregistrement de Dizzy), et il a écrit les harmonies de « Dynamo A ».

Il est difficile de mesurer l’apport de Thelonious Monk à la Nouvelle École de Jazz; il s’y rattache évidemment par son parti pris à faire du neuf, mais son imagination semble l’avoir entraîné plus loin que les autres adeptes du « new sound ».

Les années à venir nous permettront de juger si ces disques influenceront comme Monk dit l’espérer, les jeunes musiciens américains et lui amèneront de nouveaux disciples.

« Thelonious Monk » par J.J. [Jean-Jacques] Finsterwald et J.F. [Julien-François] Zbinden, Jazz-Revue in Jazz-Hot, N° 32, 15e Année (2e Série), avril 1949, p. 36.

The name of Thelonious Monk is readily associated with the famous sessions held at Minton's Playhouse (208 West 118th Street, N.Y.), where the foundations of a new style commonly called Be Bop have been developed. It is even said that his influence has been dominant, and that his contributions largely determine the leanings of this "New Sound.” The rare recordings made by Monk, in any case, reveal him to be one of the most original and most imaginative pianists we have been given the opportunity to hear.

Thelonious Sphere Monk was born in 1918 in New York [sic] into a family where no other members are musicians. Monk began experimenting with harmony and rhythm in a quartet that would have Keg Purnell for its drummer; this was in 1939. He then became the regular pianist at Minton’s in Harlem, a club run by bandleader Teddy Hill.

Despite the importance Monk has been given by the New School of Jazz (and its musicians in particular), he has not the fame of a Parker or a Gillespie. This is probably because his qualities as a performer are not on the same scale as his boundless imagination. There are reports, also, of his proverbial modesty, and a way of life that is incompatible with the exigencies to which a star is submitted: it is said that he can do without sleep for a week, even if it means sleeping three days and three nights when he succeeds in tearing himself away from the keyboard.

Monk was recorded for the first time towards the end of 1940, in the company of Charlie Christian, Joe Guy, Nick Fenton and Kenny Clarke. Those six sides were released in France by Polydor with the titles "Charly’s Choice" and "Stompin’ at the Savoy.” The sound of the recording has defects (it was made at Minton's by an amateur) and one can only guess the piano rather than hear it.

On October 19, 1944, Monk accompanied Coleman Hawkins, with Edward Robinson (b) and Denzil Best, on "Drifting on a Reed,” “Recollections," "On the Bean" and "Flying Hawk,” recorded by Joe Davis and recently published in France by Jazz Selection. The piano solos are rare and you will find the review of these titles in the French part of this issue.

So now I come to the series of recordings that Blue Note has released under Thelonious Monk's own name, and which finally allow us to hear him under good conditions. These are “Thelonious," "Suburban Eyes,” "Evonce," "Off Minor,” "‘Round about Midnight,” "Well You Needn’t,” “Epistrophy," "In Walked Bud,” "Ruby, My Dear,” and “Evidence," recorded with various musicians among whom we can mention the names of George Taitt (tp), Edmund Gregory (alto), Danny Quebec West (as), Milton Jackson (vib), John Simmons (b), Shadow Wilson (d) and Art Blakey (d), his favourite drummer.

These records show us a musician who is original to the extreme, firstly by his arrhythmia, more marked than with any other pianist, and then by his seemingly constant concern to astonish the listener; this search for the unexpected that is dear to the Be Bop style is pushed to the extreme in his playing. Monk seems to take an elegant pleasure in hesitating, both in the rhythm and in the harmony; his solos exude an unhealthy impression.

The systematic use of harmonics far from the fundamental results in agreeable, often inspired findings, but this sometimes takes him into a melodic deadlock. Thanks to his rhythmical variations he manages to keep his footing while waiting for a way out that is often no more than a timely return to a more traditional piano style, as is the case on "Thelonious." This record, incidentally, is a typical example of his style: he remains stubbornly on a note that he repeats, varying the accents of rhythm until his resources are exhausted. Instead of a single note, he sometimes chooses little motifs that he repeats to varying degrees ("In Walked Bud").

His playing is simple, his style sober and sparing; he makes very little use of chords and concentrates his full attention on a right-hand style that is a single melodic line. Despite his audacity in this, Monk uses harmonic structures that are absolutely logical, relatively simple hypotheses, and the whole tone system dear to Debussy, which he applies with pertinence.

Most of these pieces are Monk compositions (while the label attributes the paternity of "In Walked Bud" to him, one easily recognizes "Blue Skies"). He is the author [sic] of several well-known pieces—namely "Emanon" (an anagram of No Name), "52nd Street Theme" (another of Dizzy's recordings)— and he wrote the harmonies of "Dynamo A."

It is difficult to measure the contribution that Thelonious Monk has made to the New School of Jazz; he obviously relates to it by favouring the new, but his imagination seems to have taken him further than other adepts of the "new sound."

The years to come will allow us to judge whether these records will have influence, as Monk says he hopes; he and the young American musicians will attract new disciples.

Hot Club Magazine in Jazz-Hot; Surrealist poet Carlos de Radzitzky reviews Blue Note imports (NB reference to Giorgio de Chirico):

[Importation] Blue Note, Thelonious Monk Trio / Quartet / Sextet BN 549 : Ruby My Dear / Evidence - BN 542 : Suburban Eyes / Thelonious - BN 547 : Evonce / Off Minor

On a dit qu’Alfred Lion, en enregistrant Monk, commettait un suicide financier. J’espère bien qu’il n’en est rien, et je salue le valeureux et entreprenant Alfred, qui n’a pas hésité à jouer une carte certes peu commerciale, mais combien passionnante pour l’amateur de jazz. Dans un précédent « Jazz-Hot » on nous a raconté beaucoup de choses sur le fantasque Thelonious et sa musique. Ces disques constituent une excellente illustration de l’article en question. Chaque face a son charme personnel, et nous montre le Grand Prêtre du Bop sous divers aspects : tendre et romantique dans Ruby, erratique dans Evidence, où il dialogue avec Milt Jackson, plaquant d’incroyable accords derrière le vibraphone et construisant un solo d’une étonnante simplicité, mais que l’on sent limité par sa technique, curieusement buté dans ses variations d’ « Off Minor », qui tournent autour d’un complexe vaguement debussyste, original et inspiré dans ses passages en solo dans les trois autres faces enregistrées avec un petit ensemble de studio.

Les différents solistes qui l’entourent ne sont pas de grandes vedettes, mais on aurait tort de sous estimer le travail d’Idrees Sulieman à la trompette et de Danny Quebec à l’alto. Dans toutes ces faces, Blakey et Gene Ramey, à la basse, fournissent un soutien très étoffé, bien que parfois un peu bruyant.

J’aime le thème (et le titre surréaliste) de Suburban Eyes, et le solo de Monk qui s’en écarte d’ailleurs d’une manière vraiment stupéfiante, ainsi que celui du verso, où Monk construit tout son solo autour d’une note qu’il atteint de cent manières différentes, s’en écarte et y revient en laissant à sa main gauche le soin de fournir la couleur. On notera aussi, dans Thelonious, que Monk a un swing bien personnel, une consistance rythmique qui ne ressemble à aucune autre.

« American Records par Carlos de Radzitzky », Hot Club Magazine in Jazz-Hot, N° 42, 16e Année (2e Série), mars 1950, pp. 46, 47.

It's been said that in recording Monk, Alfred Lion was committing financial suicide. I really hope there's no truth in that, and I salute the valorous and enterprising Alfred, who has shown no hesitation in playing a card that is certainly not very commercial, but oh, how thrilling for jazz fans. In a previous "Jazz-Hot" we were told many things about the weird and fantastic Thelonious and his music; these records constitute an excellent illustration of the article in question. Each side carries his personal charm, and reveals the High Priest of Bop to us beneath his various aspects: tender and romantic in "Ruby"; erratic on "Evidence" where he converses with Milt Jackson, hitting incredible chords behind the vibraphone; and constructing a solo of astounding simplicity; but he's limited, you feel, by his technique; he's curiously stubborn in his variations on "Off Minor,” which revolve around a vaguely Debussy-like combination; and original and inspired in his solo passages on the three other sides recorded with a small studio-group.

The different soloists around him are not great stars but we'd be wrong to underestimate the work of Idrees Sulieman on trumpet and Danny Quebec on alto. On all these sides, Blakey and Gene Ramey, the bassist, provide very meaty support, although it is sometimes a little noisy.

I like the theme (and the Surrealist title) of "Suburban Eyes", and the solo by Monk, who moves away from it in a manner that is really stupefying, and also his solo on the other side, where Monk constructs his whole solo around one note that he reaches in a hundred different ways, and then moves away from it before coming back to it, leaving his left hand to take care of supplying its colour. One can also note, in “Thelonious," that Monk has a highly personal swing, and a rhythmical consistency that resembles no other.

[Importation] Blue Note, Kenny Pancho Hagood & T. Monk Quartet BN 1201 : I Should Care / All the Things You Are

L’ancien chanteur de Dizzy, dans deux interprétations à la Billy Eckstine, avec de-ci de-là quelques touches de Sarah Vaughan. Agréables ballades, relevées par l’intrigant accompagnement du quartet de Monk, dans lequel Milt Jackson vient jeter une note claire. Le solo de Monk sur Should est d’une aimable ingénuité.

Dizzy's ex-vocalist in two performances à la Billy Eckstine, with a few Sarah Vaughan touches right and left. Pleasant ballads, given a lift by the intriguing accompaniment of Monk's quartet, into which Milt Jackson throws a clear note. Monk's solo on "Should" has an amiable ingenuity.

[Importation] Tadd Dameron Sextet BN 1564 : Symphonette - Thelonious Monk Quartet BN 1564 : I Mean You

Symphonette, une jolie composition de Dameron, date de la même session que Jahbero, et l’étiquette présente les mêmes devinettes. Le trompette semble bien être Navarro, mais le second ténor est plus difficile à identifier. Allen Eager, sans doute. Qu’importe, les solos sont bons et l’accompagnement de Kenny Clarke particulièrement brillant. I Mean You est un thème de Monk et de Hawkins, que celui-ci a enregistré sur « Sonora », avec Navarro. L’interprétation de Monk, toute en déhanchement en accords bizarrement plaqués çà et là, en harmonies prodigieusement déroutantes, est assez intéressante, mais plutôt dure à avaler. Ce qui frappe chez Monk, c’est cette espèce d’obstination rythmique, ce perpétuel choc/écho des notes qui crée une obstination envoûtante. La représentation visuelle de la musique de Monk donne l’impression de marcher dans un tableau de Chirico.

« American Records par Carlos de Radzitzky »,Hot Club Magazine in Jazz-Hot, N° 43, 16e Année (2e Série), avril 1950, p. 37.

“Symphonette," a pretty composition by Dameron, dates from the same session as "Jahbero," and the label sets the same riddles. The trumpeter indeed seems to be Navarro, but the second tenor is more difficult to identify. Probably Allen Eager. No matter, as the solos are good and the accompaniment of Kenny Clarke particularly brilliant. "I Mean You" is a theme by Monk and by Hawkins, one that the latter recorded on "Sonora" with Navarro. Monk's playing, swaying along with bizarrely struck chords here and there, with harmonies that are prodigiously disconcerting, is interesting enough, but rather hard to swallow. What strikes you about Monk is a kind of rhythmical stubbornness, that perpetual collision/echo between the notes that creates a spellbinding obstinacy. The visual representation of Monk's music gives you the impression of walking into a painting by de Chirico.

[Importation] Blue Note, Thelonious Monk “Genius of Modern Music” LP 25 cm LP 5002 ‘Round Midnight / Off Minor / Ruby, My Dear / I Mean You / Thelonious. Epistrophy / Well, You Need’nt / Misterioso

Voilà une anthologie qui ferait bien de figurer dans toute discothèque d’amateur de jazz moderne. Nous avons déjà ici même, parlé de ces enregistrements, parus en 78 t. Profitons de leur réédition en LP pour insister sur l’intérêt considérable qu’ils représentent. Monk, dont les possibilités techniques sont fort limitées, s’est créé un style dont tout l’attrait réside dans les modifications harmoniques intrigantes, les subtilités tonales, l’articulation imprévue du phrasé, la ligne générale de l’improvisation. Son jeu, déroutant au premier abord, se révèle très attachant. Et il possède une sensibilité très délicate, comme en témoignent des œuvres telles que Ruby, ‘Round about, etc. Les formations qui l’entourent ici valent surtout par l’impeccable tenue des rythmes : y figurent des gars comme Art Blakey, Gene Ramey, etc. Dans certains morceaux, Milt Jackson s’entend splendidement avec Monk : c’est le « common spirit » qui agit. Les thèmes, pour la plupart excellents, sont tous de Monk.

C. de R.

« Jazz Collector’s Guide par Carlos de Radzitzky », Hot Club Magazine in Jazz-Hot, N° 81, 19e Année (2e Série), octobre 1953, p. 35.

This is one anthology that would do well to be in every modern jazz fan's record library. We've already talked about these recordings in this same column, issued as 78rpm records. Let's take advantage of their reissue on LP to emphasize the considerable interest that they represent. Monk, whose technical possibilities are strongly limited, has created a style for himself whose attraction lies entirely in the intriguing harmonic modifications, the tonal subtleties, the unexpected articulation of his phrasing, and the general line of his improvising. His playing, at first sight disconcerting, turns out to be very endearing. And he has very delicate sensibilities, as evidenced on works such as "Ruby" and "‘Round about..." etc. The ensembles surrounding him here have merit, particularly in the impeccable manner the rhythms are kept: present here are characters like Art Blakey, Gene Ramey etc. On some pieces Milt Jackson gets along splendidly with Monk: the "common spirit" is in action. The themes, most of them excellent, are all by Monk.

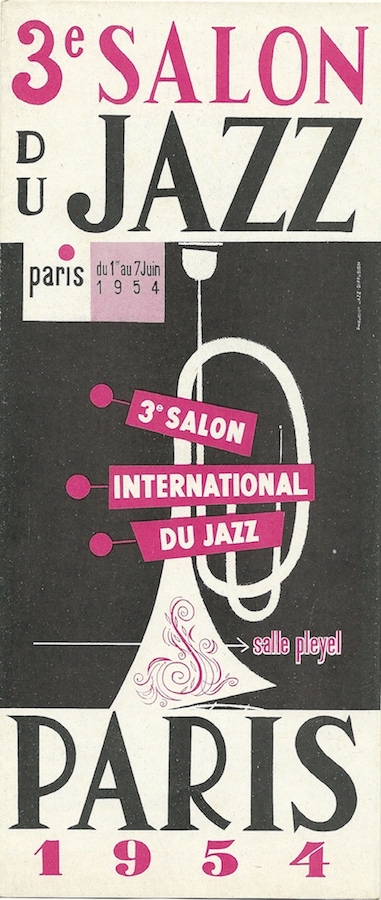

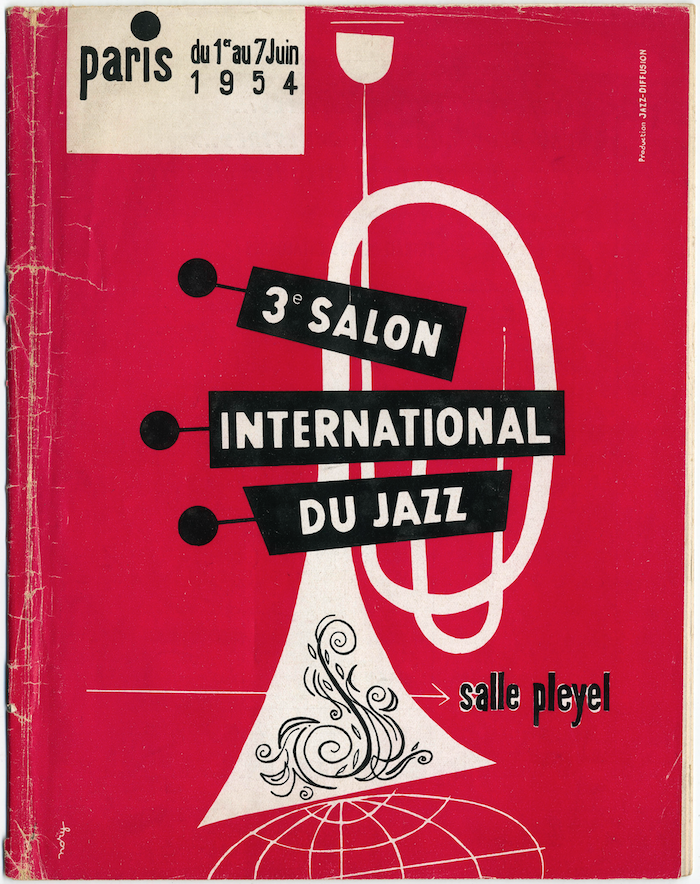

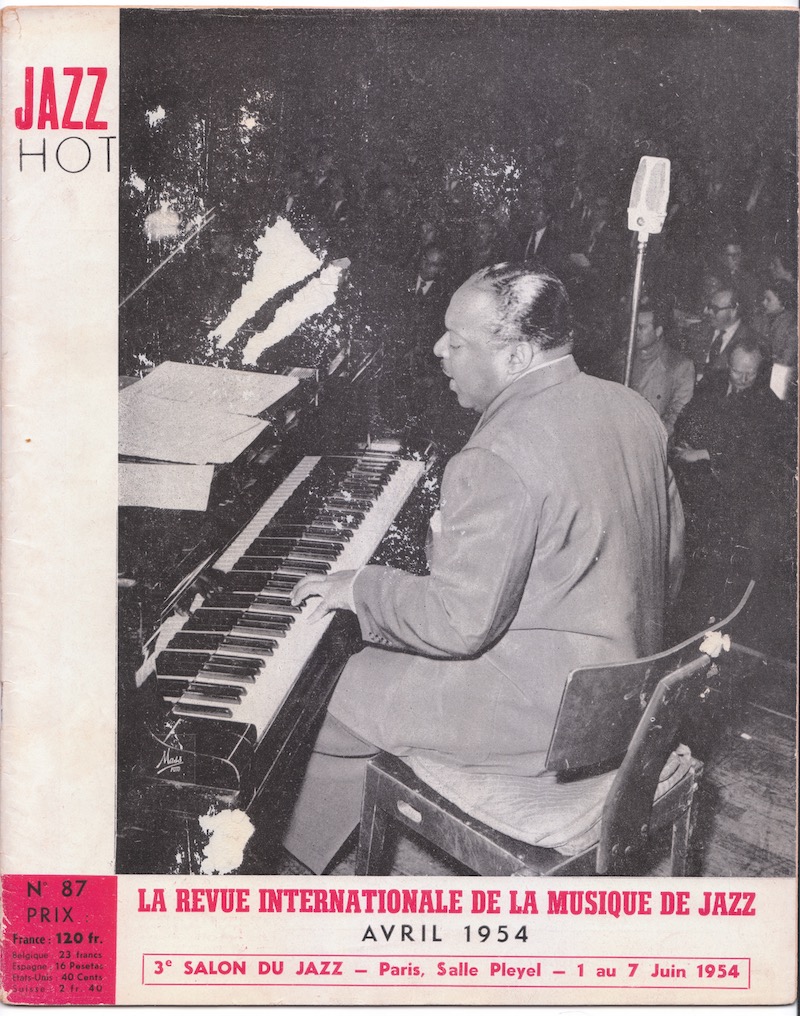

Announcement of the 3rd Salon du Jazz

Program, Promotion and Publicity Before May 31

Chronology

« …Nous sommes heureux d’annoncer que le 3e Salon du jazz se déroulera en mai 1954 à Paris, selon une formule entièrement nouvelle. Nous donnerons ici toutes précisions voulues en temps utile… »

[Editorial] « Le 3e Salon du jazz en mai 1954 », Jazz-Hot, N° 82, 19e Année (2e Série), novembre 1953, p. 7.

...We are happy to announce that the 3rd Salon du Jazz will take place in Paris in May 1954 with an entirely new format. Here you will be able to find all the information you want in due course…. "

« Le IIIe Salon du jazz »

« Le 3e Salon du jazz qui clôturera la saison 1953-1954, se déroulera du 30 mai au 7 juin, à la Salle Pleyel. Si le salon proprement dit n’a pas, peut-être, l’ampleur des précédents, par contre les spectacles prévus pendant ces huit jours, avec la participation de plusieurs groupements américains, seront dignes des précédents Festival de jazz… »

« Jazz-Hot Magazine : En France », Jazz-Hot, N° 85, 20e Année (2e Série), février 1954, p. 21.

"The III rd Salon du jazz"

"The 3rd Salon du jazz which closes the 1953-1954 season will take place from May 30 to June 7 at the Salle Pleyel. While the season proper is perhaps not on the same scale as its predecessors, on the other hand the shows planned over these eight days, with several American groups participating, will be worthy of previous Jazz Festivals…."

« Le 3e Salon du jazz se tiendra du 1er au 7 juin 1954 à la Salle Pleyel, c’est à-dire pendant la dernière semaine de la Foire de Paris qui se termine avec les vacances de la Pentecôte; cela permettra sans nul doute à de nombreux amateurs de province et de l’étranger de faire le déplacement de Paris… »

[Editorial] « 3e Salon International du jazz », Jazz-Hot, N° 86, 20e Année (2e Série), mars 1954, pp. 7, 20, 21.

"The 3rd Salon du Jazz will be held from June 1–7, 1954 in the Salle Pleyel, that is, during the last week of the Paris Fair which ends with the Whitsun holiday; there's no doubt that this will allow numerous fans from the provinces and abroad to make the trip to Paris…."

[3 Illustrations par David Gil des décors du] « Paris - 1 au 7 juin 1954 : 3e Salon International du jazz…l’immense Cabaret tel qu’il apparaître aux visiteurs de cette grande manifestation…2 aspects du Hall de la Salle Pleyel transformée en « Cité du jazz ».

« Jazz-Hot Magazine », Jazz-Hot, N° 86, 20e Année (2e Série), mars 1954, p. 20.

[3 Illustrations by David Gil of the scenery of] "Paris - 1 to 7 June 1954: 3rd International Jazz Salon…. the immense Cabaret as it will appear to visitors to this great event…. 2 aspects of the hallway inside Salle Pleyel transformed as "City of jazz.”

First Name Mentioned

« Merci de sa lettre à C. B. Peytavin. —Il me demande la chose suivante : « Pour le 3e Salon du jazz, on parle de faire venir des gens à la mode du jour, c’est-à-dire surtout Gerry Mulligan et ses joyeux plaisantins … »

« Revue de Presse par Boris Vian », Jazz-Hot, N° 87, 20e Année (2e Série), avril 1954, p. 19.

"Thanks to C.B. Peytavin for his letter.—He asked me the following: "For the 3rd Jazz Salon there is talk of bringing over people who are fashionable at the moment, in other words above all Gerry Mulligan and his cheerful bunch of jokers…."

Thelonious Monk Mentioned for the First Time

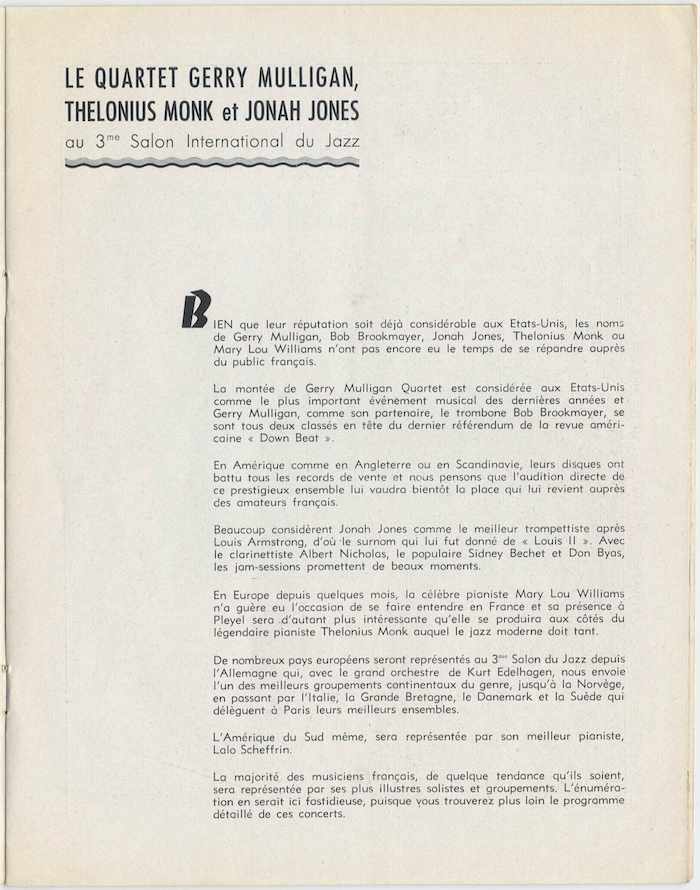

“Paris, Wednesday [April 7],—Thelonious Monk, pioneer bop pianist, has definitely been signed up for the Salon de Jazz (the Paris Jazz Fair), which will be held from June 2 to 7.

Negotiations are also proceeding for the Gerry Mulligan Quartet (with a trombone in place of trumpeter Chet Baker), former Cab Calloway trumpet man Jonah Jones, and the orchestra of Germany’s ‘Stan Kenton,’ Kurt Edelhagen.”

“Thelonious Monk for Paris Jazz Salon,” Melody Maker, Vol. 30, N° 1073, April 10, 1954, front page.

Press Release and First Draft Program

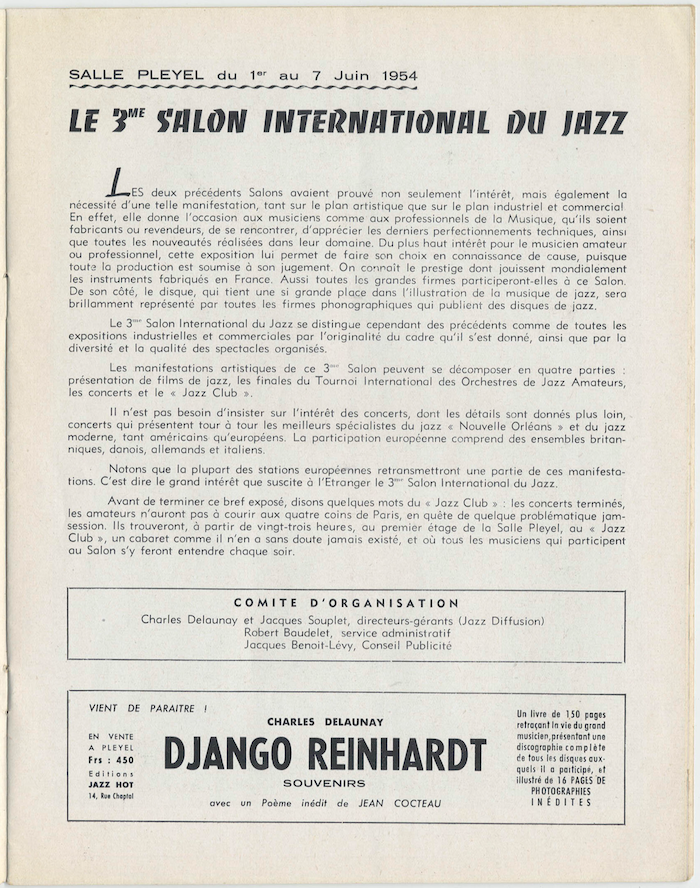

Exposition industrielle et commerciale

Le IIIe Salon du Jazz se distinguera des précédents, comme d’ailleurs de toutes les expositions industrielles et commerciales, par son aspect exceptionnel. En effet, l’ensemble des stands sera présenté suivant un thème unique : un décor inspiré par les vieux quartiers de la Nouvelle-Orléans.

Les deux précédents Salons avaient prouvé non seulement l’intérêt, mais également la nécessité d’une telle manifestation, tant sur le plan artistique que sur le plan industriel et commercial. En effet, elle donne l’occasion aux musiciens comme aux professionnels de la Musique, qu’ils soient fabricants ou revendeurs, de se rencontrer, d’apprécier les derniers perfectionnements techniques, ainsi que toutes les nouveautés réalisées dans leur domaine. Du plus haut intérêt pour le musicien amateur ou professionnel, cette exposition lui permet de faire son choix en connaissance de cause, puisque toute la production est soumise à son jugement.

On connaît le prestige dont jouissent mondialement les instruments fabriqués en France. Aussi toutes les grandes firmes participeront-elles à ce Salon. De son côté, le disque, qui tient une si grande place dans l’illustration de la musique de jazz, sera brillamment représenté. Toutes les firmes phonographiques, qui s’intéressent de plus en plus à cette musique, seront là. Un effort particulier sera même fait par certains éditeurs puisque, à l’occasion du Salon, les amateurs pourront se procurer des enregistrements encore inédits.

Grâce à sa présentation spectaculaire et à son ampleur, cette exposition attirera également le grand public et contribuera ainsi à mieux faire connaitre la musique de jazz et, par conséquent, à développer les industries et commerce qui s’y rattachent.

Manifestations artistiques

Toutes les manifestations du IIIe Salon du Jazz se dérouleront dans le cadre même de la Salle Pleyel.

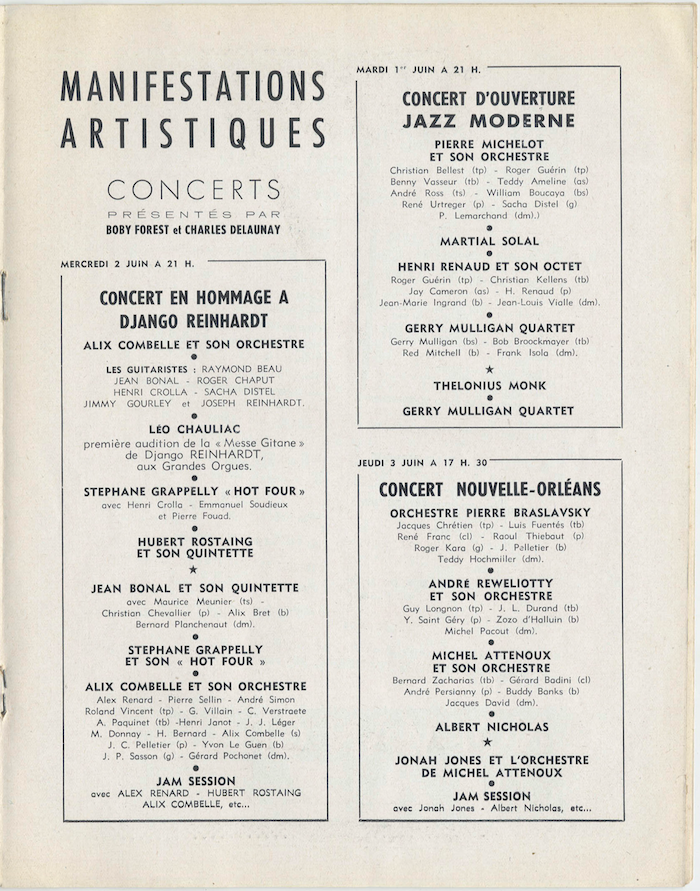

De nombreux concerts auront lieu chaque jour dans la grande salle avec les différents solistes spécialement venus des États-Unis : Thelonious Monk, l’un des principaux promoteurs du jazz contemporain, le trompettiste Jonah Jones et « la plus sensationnelle révélation de 1953 », le quartette de Gerry Mulligan. Bien entendu, le populaire Sidney Bechet, Mary Lou Williams, Albert Nicholas, Don Byas et plusieurs autres artistes américains actuellement en Europe se joindront à ces vedettes. L’Italie nous enverra le « Roman New Orleans Jazz Band », l’Allemagne son meilleur orchestre : celui de Kurt Edelhagen, avec ses dix-sept musiciens, etc. Plusieurs groupements français sont également prévus.

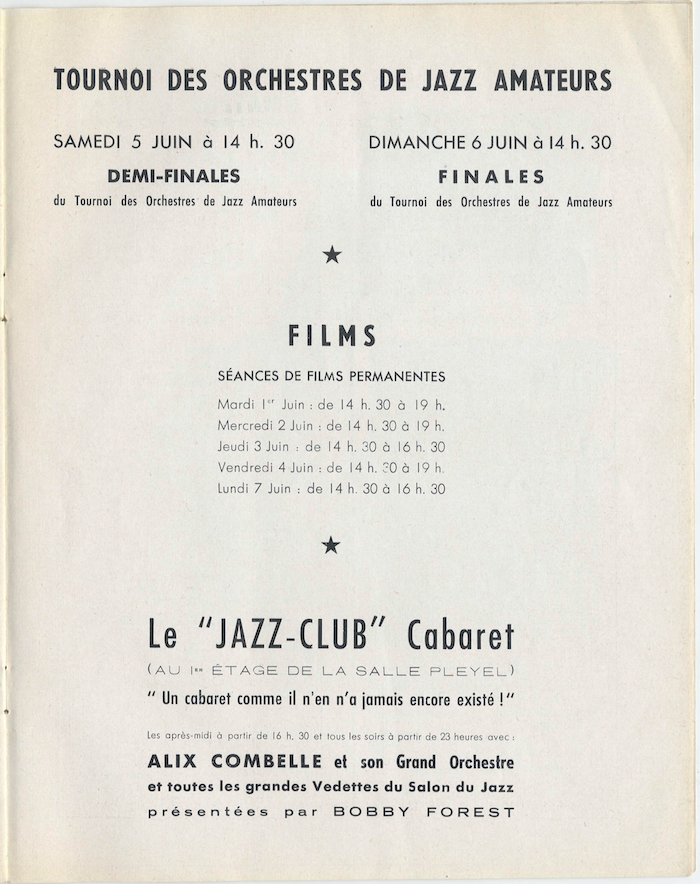

Les demi-finales et finales du Tournoi des Orchestres amateurs se dérouleront les 5 et 6 juin, en matinée.

Les jours de semaine, des films seront projetés en matinée.

Un grand cabaret permettra aux amateurs, les concerts terminés, d’entendre les musiciens dans une ambiance différente. Ils n’auront pas ainsi à courir les quatre coins de Paris à la recherche de problématiques Jam sessions.

De nombreux voyages par groupes, facilités par les vacances de la Pentecôte, sont organisées, venant aussi bien de l’étranger que de province.

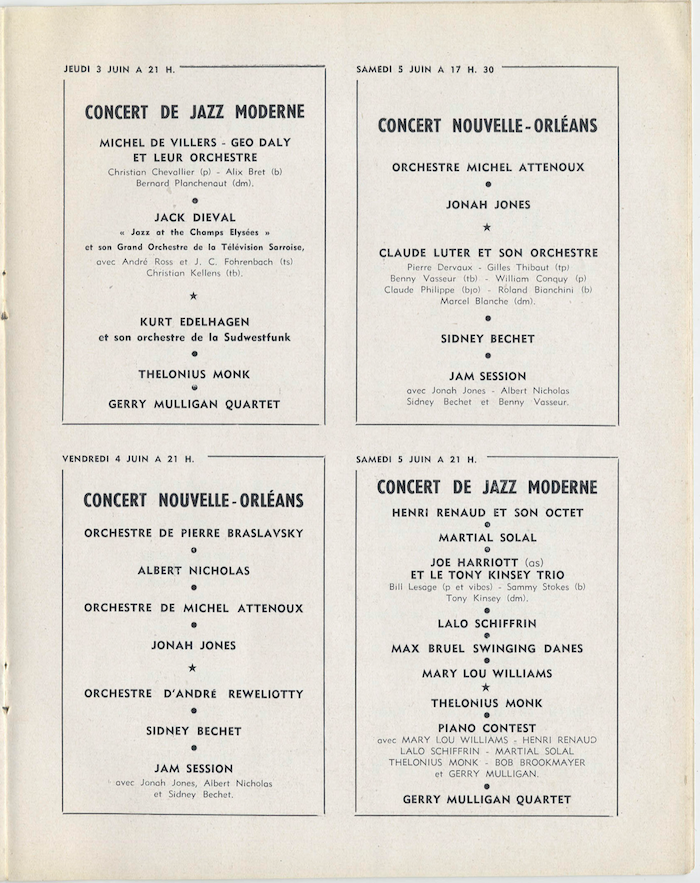

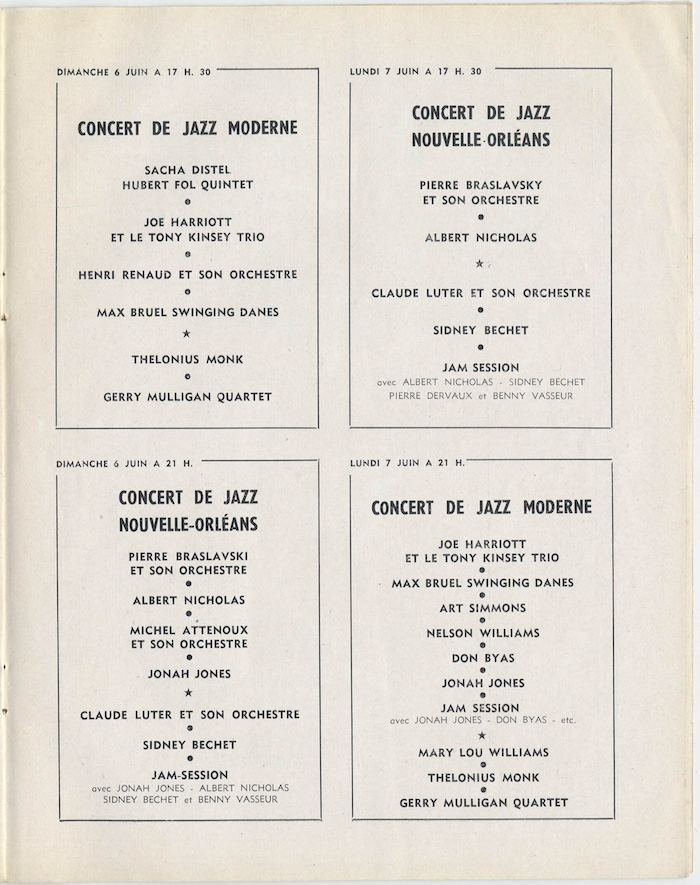

« 3e Salon International du Jazz : Sous le haut patronage de Monsieur le Ministre de l’Industrie et du Commerce, Paris, 1er au 7 juin 1954, Salle Pleyel », Jazz-Hot, N° 88, 20e Année (2e Série), mai 1954, pp. 8, 9.

Industry and Commerce Exhibition

The 3rd Jazz Fair will stand out from previous editions, as does every industrial and commercial exhibition by the way, due to its exceptional appearance. All the stands will be decorated based on a single theme: the decor is inspired by New Orleans' French Quarter.